It’s been three weeks since the start of the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar, and even if football matches have been the main topic of conversation, human rights have not been far behind. In this second part of our series “Red Card on Digital Rights,” SMEX and Ranking Digital Rights (RDR) dig further into the main issues of concern when it comes to the internet and digital surveillance in Qatar.

Massive Surveillance

Thirty-two teams have played since the tournament began, watched by 1.2 million visitors and more than 15,000 surveillance cameras. Far from fearing criticism, the country’s authorities have proudly touted the tournament’s surveillance and security systems. Niyas Abdulrahiman, Chief Technology Officer (CTO) of Aspire Zone Foundation, in charge of stadium technology during the 2022 FIFA World Cup, told AFP in August: “We have eyes on the ground, we can view all of the 15,000 cameras across the eight stadiums.” This, he has claimed, “is the future of stadium operations.”

As far back as seven years ago, Qatar’s main telecom company Ooredoo announced plans to create the “World’s Best Smart Stadiums,” with “full access to control systems for an integrated range of functions such as video surveillance.” Like a state-of-the-art panopticon, everything is viewed from its inspection house: in this case, the ASPIRE Control & Command Center. Here, more than 100 technicians monitor and control all security, protection, and operational systems for the tournament’s eight stadiums and nearby streets.

What FIFA organizers in Qatar don’t talk about, however, are the human rights implications of the technology they advertise as key to their next-generation stadiums. We don’t know, for example, for how long people’s pictures will be kept by their technology, or how people’s facial biometric data will be linked with other personal information to identify the individuals recorded by these thousands of cameras.

The ASPIRE Control and Command Center pictured from inside. Via Aspire Zone Youtube video.

The ASPIRE Control and Command Center pictured from inside. Via Aspire Zone Youtube video.

A lack of transparency from Qatari telcos

As mentioned in part one of this series, Ooredoo is owned primarily by entities tied to the Qatari government. Most visitors to the country for the World Cup will be connecting to networks through this company, which has offered a free SIM card with the Hayya app.

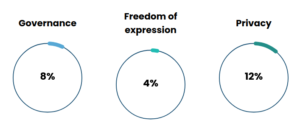

Ranking Digital Rights has evaluated and ranked Ooredoo in its Corporate Accountability Index—which looks at more than 250 aspects of a company’s policies that affect people’s human rights, focusing on corporate governance, freedom of expression, and privacy—since 2017. In this year’s inaugural Telco Giants Scorecard, Ooredoo came in last place for the fifth consecutive time, highlighting its glaring lack of policy transparency. This year marked the first time that Ooredoo committed to “safeguarding human rights,” as part of its inaugural ESG report, but the company did not expand on what this commitment entails. Ooredoo makes neither a commitment to net neutrality nor does it share anything about its process for responding to government shutdown orders, or how many such orders it received or complied with. Ooredoo failed to provide any information about how it handles government demands for content takedowns, account restrictions, or user information.

Above are Ooredoo’s scores in the three main categories RDR ranks as part of its 2022 Telco Giants Scorecard. You can read the full Ooredoo report card here.

There is an alternative to the main Qatari mobile provider: Vodafone, the British multinational telecom company, has a subsidiary in Qatar. Unfortunately, it’s making the same foul plays as Ooredoo. Vodafone Qatar’s Terms and Conditions and Data Privacy Policy provide insufficient transparency about how the company responds to government demands to restrict access to content and accounts and shut down its networks. Similarly, it discloses nothing about how it handles government demands for user information, stating only that it may disclose information about users “to legal or regulatory agencies in order to meet any requirements of applicable laws in the state of Qatar, including regulations of national security agencies.” This broad language gives the company wide leverage to participate in potential government overreach. Finally, Vodafone Qatar users are in the dark about how their information is handled. The company provides a non-exhaustive list of the types of user information it collects. However, nothing is disclosed about what information is shared and inferred. It also does not specify how long it retains user information.

The opaque policies of the Hayya app

Spectators who wish to access the tournament are required to obtain a Hayya Card, which can be obtained through the Hayya portal or app, launched by the Supreme Committee for Delivery and Legacy (SC), the official committee the Qatari government has charged with the planning and operation of the games. The Hayya Card provides fans with an entry permit into Qatar, entry into stadiums, and other benefits such as free transport and a free SIM card.

Hayya’s policies have important shortcomings and lack transparency, which can pose notable risks to fans’ right to privacy. In November, SMEX released a report exploring Hayya’s remedies for privacy-related grievances; access to and notification of changes to privacy policies; user information collection, sharing, inference, and retention; targeted advertising and user tracking; response to government surveillance demands; and security. The results were as follows:

Weak mechanisms for addressing privacy concerns

The mechanisms available through the Hayya app and portal to address users’ privacy concerns, potential grievances, and eventual corresponding remedies, were found to be deficient. The mechanism for lodging complaints merely refers to the possibility of doing so through the state’s legal system, in particular via the Ministry of Transport and Communications. But since a complaint against the app constitutes a complaint against the SC, also a state entity, a conflict of interest could arise. In addition, to make use of grievance mechanisms and submit complaints, users need to contact the SC via email addresses, but these are hard to find. European fans are additionally protected, however, thanks to the GDPR, so they can also lodge complaints with the Information Commissioner’s Office in the UK or with EU data protection authorities.

No notification of changes to privacy policies

No notification of changes to privacy policies

When accessing the platform through the Hayya website, the privacy policy is easy to find and the language used is not overly complicated. However, the accessibility of the policy does have serious flaws: It is only available in English, and therefore not available in Arabic (the primary language spoken in Qatar), nor in other languages widely spoken by football fans from around the world.The SC does not disclose that it directly notifies users about changes to its privacy policy or to its Cookie Notice and it was not clear the SC maintained a public archive or change log.

User information handled with opacity

The SC is transparent about what user information it collects and how, mentioning specific categories of user information and even providing examples. On the other hand, there is no commitment from the SC to delete all user information after a Hayya account is terminated. It is only stated that if user information is no longer needed it will either be “irreversibly” anonymized or “securely” destroyed. This vague language means the SC could retain data it does not need for longer periods of time, or even indefinitely.

Users lack control over targeted advertising

It is unclear what the SC’s advertising targeting rules are and how they are enforced. The targeting parameters include users’ browsing habits and their interests. The language used is not comprehensive and there is no mention of prohibited targeting parameters. Advertising opt-out/opt-in options includes only the ability to reject “marketing” via direct contact as well as “in-app marketing,” but there are no opt-out options for the Hayya portal.

In a nutshell: Rather than a truly privacy-respecting policy, the Hayya app and portal require users to actively engage in privacy-protecting measures that are only effective for a limited number of targeted advertising and tracking processes. Qatari law does not regulate targeted advertising or tracking.

Vague process for handling government surveillance demands

There is scarce information about how the SC will respond to surveillance demands from non-judicial government agencies and courts. It is also unclear how the SC handles demands from foreign jurisdictions. The privacy policy explains merely that it may share user information “in order to comply with any legal obligation” inside or outside Qatar. No data is provided regarding the number of government demands received for user information, foreign or domestic, and it is also unclear if the SC plans to publish such data at a later date.

vague security policies and measures

vague security policies and measures

The SC lacks transparency about security policies and measures. There is no disclosure regarding measures to limit and monitor employee access to user information, no mention of a security team conducting audits of Hayya, and no indication that it commissions third parties to conduct such audits. It provides no mechanism through which security researchers can report vulnerabilities or any commitment not to pursue legal actions against these researchers. The SC’s process for dealing with data breaches that may occur on the Hayya app and portal is equally unknown. The SC does not disclose any use of essential user safety measures.

The full report of “Mandatory App, Opaque Policies” by SMEX can be accessed here.

Amid a great deal of surveillance and data collection ongoing in Qatar during the World Cup, a total lack of transparency is heightening risks to digital rights. This makes it impossible to ascertain to what extent Qatar’s actions stem from a desire to ensure high levels of security during the event versus whether it’s purposefully attempting to carry out surveillance. Either way, it’s clear the country has put far more consideration into creating an all-encompassing security apparatus than it has into safeguarding digital rights of any kind. Fortunately, both RDR’s Ooredoo Scorecard and SMEX’s Hayya report provide realistic recommendations for steps that can be taken to ensure respect for human rights. There’s no excuse for hosting major events with this level of massive surveillance, especially with such opaque policies.

Fans can likely expect some more amazing football matches before this World Cup ends, after which RDR and SMEX will return in early 2023 with a retrospective on the lessons learned for digital rights during the tournament and some thoughts about how we might mitigate risks for future ones.