Advancements in technology in the past decade have led tech companies to wield unprecedented power over the online sphere. Despite our digital progress, the internet remains poorly regulated and continues to subject its users to invasions of privacy and restrictions to online speech.

For the past eight years, Ranking Digital Rights (RDR) has pushed companies to uphold their obligations to human rights through the annual RDR Corporate Accountability Index, a body of public interest research that evaluates the transparency of prominent tech companies’ policies and practices, especially those affecting people’s rights to free expression and privacy. The Index also ranks companies’ performances against that of their competitors.

RDR Categories and Indicators

The Index evaluates companies on 58 indicators encompassing governance, freedom of expression and information, and privacy, as articulated in the UDHR, the ICCPR, and other international human rights instruments.

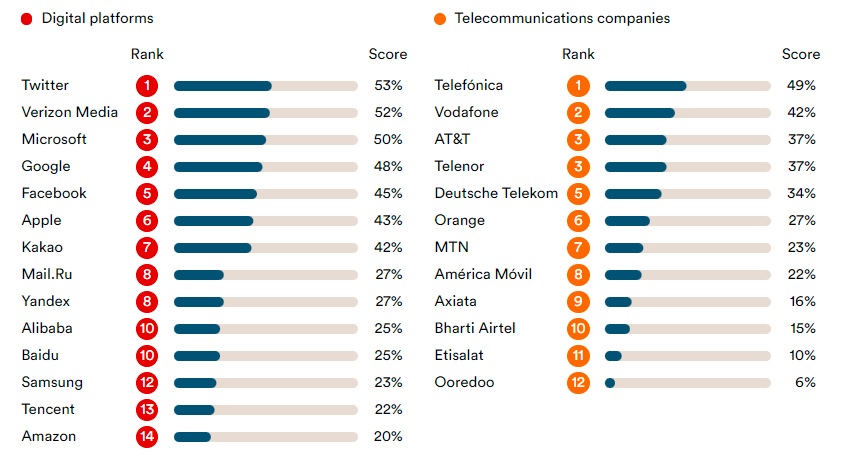

2020 Ranking Digital Rights Corporate Accountability Index.

Indicators in the governance category evaluate aspects such as a company’s public commitment to human rights, governance management and oversight over freedom of expression and privacy, and human rights due diligence. Indicators in the freedom of expression and privacy categories seek evidence of the companies’ transparency regarding private rules and commercial practices, including accessibility to policies, clear terms of service and sound enforcement, ad content and ad targeting rules and enforcement, clear policies describing use of algorithmic systems and transparent disclosure of how these companies respond to government and private demands. Under privacy, the RDR Index assesses how companies determine, communicate, and enforce private rules and commercial practices that affect users’ privacy. These include the collection and handling of users’ data, implementation of internal security measures, and responding to government and private demands to hand over users’ information.

Etisalat and Oredoo barely made the 10% mark on the RDR List

Digital platforms and telecommunications companies are both under the Index’s radar. In 2020, Twitter, Google and Microsoft, scored an overall 53%, 50% and 48%, respectively. As for telecommunications companies, Spanish Telefonica, Vodafone, and Orange scored 49%, 42% and 27%, respectively. While the above statistics may seem low, these are in fact among the highest rankings in RDR’s report. Some of the most advanced telecommunications companies in the world failed to even cross the passing mark on RDR’s Index. These poor results demonstrate the urgency for an accountability system that forces tech giants to respect and promote digital rights in their policies and practices.

“The most striking takeaway is just how little companies across the board are willing to publicly disclose about how they shape and moderate digital content, enforce their rules, collect and use our data, and build and deploy the underlying algorithms that shape our world,” cautioned Amy Brouillette, Senior Research and Editorial Manager of the RDR Index.

On a regional level, RDR reviewed two telecommunications companies from Arabic-speaking countries, Etisalat and Ooredoo, scoring 10% and 6%, respectively. Etisalat is an Emirati-based telecommunications services provider with 149 million subscribers in 15 countries across the Middle East, Africa, and Asia. It wasn’t until 2020 that the company publicly published its privacy policy, a basic privacy requirement for a telecommunications company operating on a multinational level. At the same time, Etisalat failed to provide a transparent description about how the company handles users’ data, especially its policies on sharing and retaining that information with the Emarati government or private actors.

It only disclosed that it may share collected data with legal authorities, without a clear explanation about how it shares it, nor the types or names of third parties involved. Moreover, Etisalat did not disclose its process for handling government and private demands to remove content and accounts or to access user data:

“To be more specific, we may disclose your personal information to third parties if we are under a duty to disclose or share your personal information in order to comply with any legal obligation or to protect the rights, property, or safety of Etisalat, our customers or others.”

It is worth noting that while there is no law prohibiting Etisalat from communicating how it handles requests:

“We may be required to disclose your personal information or legally intercept the services to comply with the laws of the UAE or the express instructions of a competent authority (such as the Telecommunications Regulatory Authority) or where it is deemed necessary in the interests of public or national security.”

Etisalat’s counterpart Ooredoo, headquartered in Qatar and majority-owned by the Qatari government, received the lowest score of all telecommunications companies evaluated in the Index and was only slightly outperformed by Etisalat. Despite its implementation of a few changes following RDR’s assessment in 2019, Ooredoo scored 4% in both governance and freedom of expression, and 8% in privacy. Regarding governance, it committed to respecting privacy as a “legal right” in Qatar ensured by Article 37 of its constitution, falling short of committing to international human rights standards of privacy. There was also little evidence that it practiced due diligence in assessing the human rights impacts or risks associated with its operations, products, or services. No systematic engagement with stakeholders that represent, advocate on behalf of, or are people whose privacy and freedom of expression and information are directly impacted by the company. Finally, regarding remedies, the telecom company did not provide users with grievance or remedy mechanisms to address their privacy and freedom of expression and information complaints. The mechanism offered in its Customer Service Charter, broadly named “Customer Service Behavior,” is offering very little guidance for users who want to file complaints based on potential violations of their rights.

Regarding freedom of expression, Ooredoo did not disclose data about content and account restrictions to enforce its terms of service and did not commit to notifying users of such restrictions. This violates users’ freedom of expression as the company will not notify users of restrictions enforced on their account in order to enforce its own terms of service. The company also failed to provide policies outlining its ad content and ad targeting practices, in addition to other policy information elucidating how it would respond to a government shutdown demand.

These figures reflect the consequences of government control over telecommunications companies: lack of transparency regarding handling user information and absence of respect for users’ freedom of expression and privacy violate international human rights standards. In each case, failure to publish evidence showing proper assessment of human rights risks demonstrates how little these tech companies are actually doing to protect users’ basic digital rights.

Government owned telecommunications companies risk being tools of power in the hands of authoritarian governments who regularly violate citizens’ rights with absolute impunity, from internet shutdowns to government-sponsored surveillance. Lebanon is a notable example among Arabic-speaking countries, where both telecommunication companies, Touch and Alfa, are owned by the Lebanese government and are subject to strict controls. In addition, a single company known as Ogero owns the infrastructure for phone and internet connections and consults privately with the government to determine Wi-Fi pricing. Another example is India, where the government utilizes internet shutdowns to limit freedom of expression and suppress its critics. Amid more frequent protests in the past years, the number of internet shutdowns in India has jumped to 121 in 2019. In Tunisia, the government has some control over telecommunication companies since it owns stakes in two of the country’s three major telecommunication companies: Tunisie Telecom and Orange Tunisie.

Let’s Raise Our Standards

In conclusion, tech companies need to be actively increasing their efforts in protecting and upholding digital rights by implementing clear and transparent policies prepared by qualified experts. Simultaneously, some responsibility falls on users to self-inform about these violations before agreeing to share information with these entities. In many countries, NGOs and activists alike are working on increasing efforts in advocacy for legal reform in countries where governments own or control telecommunication companies and transform the legal system into one that protects citizens’ digital rights. Digital platforms must be more transparent about their policies, laws and regulations, and they have to present them to the public in less complex language. Their terms of service and privacy policies must be straightforward and easy to understand, thus making sure each user is properly informed about their rights, the nature of the data stored, and how it is processed.