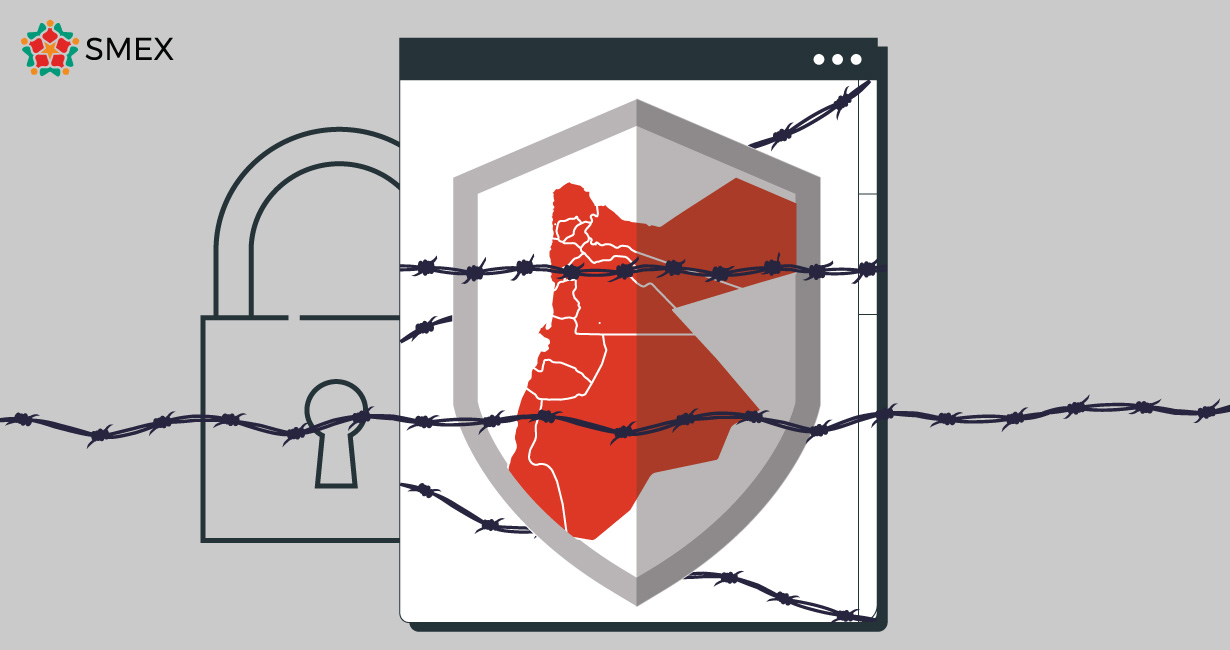

SMEX, along with the Jordan Open Source Association (JOSA), Access Now, and 19 other organizations, call on the Jordanian government to retract a proposed cybercrimes law currently under consideration in parliament. We are concerned the bill would have detrimental effects on free speech online, compromise the right to anonymity for internet users, and grant new powers to regulate social media, potentially leading to an alarming increase in online censorship.

The draft law includes 41 articles intended to regulate people’s activities on the internet, especially regarding cases pertaining to spreading misinformation, libel and defamation, publishing and rumors.

The Prime Minister and other cabinet members are entrusted with implementing the provisions of this law, meaning that no specific ministry or official entity is responsible for enforcing or considering the law. It is an independent piece of legislation that is not related to any other law, and it revokes the Cybercrime Law No. 27 of 2015.

In fact, the new law is a stricter version of the latter, as it imposes “irrational and unrealistic” penalties disproportional to the “crimes” mentioned therein, according to a press interview with Jordanian MP Yanal Freihat.

Irrational Provisions and Penalties

The new law requires companies that own social media platforms abroad to open offices in Jordan. This would allow them to respond to requests and notices issued by judicial and official authorities.

Article 37 of the draft law stipulates that if social media platforms outside Jordan fail to abide by this requirement, they will “receive a notice from the Telecommunications Regulatory Commission urging them to comply within a maximum period of six months as of the date of the notice.”

The TRC may then take several measures, including banning ads on those platforms in Jordan for 60 days and gradually reducing their bandwidth. In other words, the draft law legalizes the practice of throttling, i.e. obstructing citizens’ access to the internet and social media.

Some articles of the draft law include the same malpractices that are often found in Cybercrime Laws. For instance, Article 15 punishes “anyone who intentionally sends, resends, or publishes data or information containing false news, libel, defamation, or slander against any person via the internet, IT networks, information systems, websites, or social media platforms to at least three months of imprisonment and a fine of no less than 20,000 Jordanian dinars and no more than 40,000 Jordanian dinars.”

In addition, Article 17 stipulates that “anyone who intentionally uses the internet, IT networks, information systems, websites, or social media platforms to publish content that provokes strife, undermines national unity, incites or justifies violence or hatred, or disrespects religions shall be punished with one to three years of imprisonment and a fine of no less than 25,000 Jordanian dinars and no more than 50,000 Jordanian dinars.”

In reality, these harsh punishments, which include imprisonment and exorbitant fines (given to the State Treasury rather than the victim), are alarming since they apply to regular social media users.

Minister of Government Communications Faisal Shboul said in a statement that the Draft Cybercrime Law aggravated previous financial penalties since 16,000 cybercrime complaints were received in 2022 and another 8,000 in the first six months of 2023.

The government used these numbers as a pretext to develop a draft law that further undermines freedom of expression. This was confirmed by statements from Minister of State for Legal Affairs Nancy Namrouqa, who considered that the previous version of the Cybercrime Law “failed to suppress violations and breaches.”

Expert in media laws Yahya Choucair told SMEX that the government did not disclose the law until after the deadline for submitting shadow reports for Jordan’s Universal Periodic Review before the Human Rights Council, which is due in February.

“Anyone who reads the provisions of Articles 15, 16, and 17 of the Cybercrime Law will realize that the severe fines, which reach 70,000 Jordanian dinars, completely nullify the right to freedom of opinion and expression,” Choucair warned.

Jordan has ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which stresses that the freedom of opinion and expression is absolute and can only be restricted in exceptional cases.

However, many articles under the draft law violate this principle, as they enable authorities to deny citizens the right to communicate and access information. According to the Jordanian government, international treaties and conventions “transcend local laws and prevail over them, should the two conflict, and that no domestic law shall be invoked against international conventions.”

In Jordan, international treaties were given priority over domestic laws under certain circumstances. These precedents include Jordanian Court of Cassation Decision No. 1477/2005 dated September 7, 2005, Decision No. 4309/2003 dated April 22, 2004, and Decision No. 1824/2995 dated October 25, 2005.

Given this background, the same approach should be applied to the new cybercrime law which obviously conflicts with international conventions on human rights.

Ambiguous Provisions

The new draft law has faced criticism not only from legal experts and human rights advocates but also from several MPs, ministers, and government officials. They have expressed their discontent with the proposed law’s numerous transgressions. MP Hassan Al-Riyati described the law as being a “coup against democracy in Jordan,” while MP Ahmad Qatawnih demanded that the draft law be rejected, considering that “many issues have been resolved as a result of being shared on social media.”

MP Saleh Al-Armouti believes the draft law “goes against reason and intellect and reneges on reforms,” adding that “the government is trying to limit people from defending themselves while reinforcing customary provisions that harm the nation and its citizens.”

Similarly, MP Farid Haddad argued that “the law marks a clear setback in terms of protecting public freedoms,” demanding the House of Representatives to reject it and “send it back where it came from.”

The law includes brief and ambiguous definitions of a number of terms, including data, information system, IP address, which will no doubt be used to press arbitrary charges against users.

To make matters worse, Minister of Digital Economy and Entrepreneurship, Ahmad Hanandeh, insisted that “there is not one article in the new law that restricts freedom.” He emphasized that it focuses solely on cybercrimes and related incidents, dismissing claims that it encroaches on people’s freedoms as baseless.

The problem is that, when taken at face value, this statement cannot be considered misleading due to the ambiguous and loose terminology used to formulate the laws’ articles.

Head of the Legal Unit at SMEX Marianne Rahme confirms that the new draft law is the latest attempt by Jordanian legislators to control the digital realm: “In their pursuit to regulate tech companies, Jordanian lawmakers have followed in the footsteps of their counterparts in Saudi Arabia. The companies are compelled to open offices within the Kingdom to gain entry into the lucrative Saudi market.”

The wording of the law is very unclear, leaving much room for interpretation. It is uncertain how enforcement will take place. The concern is the lack of understanding regarding IP addresses and their functioning,” Rahme warned. “Moreover, the law legalizes internet shutdowns and numerous other violations. Should this law be approved, it could set a dangerous precedent, potentially encouraging other governments in the region to adopt similar chilling legislation.”

The board of the Jordan Press Association expressed its rejection of several amendments to the Draft Cybercrime Law, seeing how “it contributes to silencing people and restricting press and public freedoms.” The Association believes the law ought to have reinforced the achievements made at the level of freedoms in Jordan.

The board also called upon the Legal Parliamentary Commission to review the draft law drastically, reduce the aggravated punishments, and remove the loosely worded and ambiguous provisions that may further erode public freedoms in the country.

“The draft law is a setback at the level of freedoms,” the board added. “For instance, the legislators have placed more emphasis on character assassination, aggravating the punishments for issues related to freedoms and reducing them in the case of violations undermining social peace.”

The board also remarked that the draft law granted excessive powers to the Public Prosecution by giving it the right to prosecute conventional crimes without the need for a complaint or personal claim if the crime was committed against an official authority or body.

Jordan ranks 146th (out of 180 countries) on the 2023 World Press Freedom Index published by Reporters Without Borders, which explains that “[Jordanian] media professionals censor themselves and respect the implicit red lines around certain subjects.”

Jordan also ranked 47th out of 100 in terms of freedom on the net, according to Freedom House’s 2022 report.

This is not the first time that Jordanians have been concerned about the government’s tendency to suppress speech and deny them access to social media. The latest such incident was Jordan’s TikTok ban, enforced since December 2022, as well as the blocking of satirical website Al-Hudood on July 4.

The Euro-Med Human Rights Monitor, a Geneva-based independent organization, had called upon the Jordanian authorities to lift all restrictions on freedom of expression and opinion in the country, as well as repeal all legal provisions that could be used to undermine liberties.

“The procedures, practices, and laws that limit freedom of opinion and expression have resulted in an ongoing state of self-censorship among bloggers and opinion holders, as a large number of them refrain from publicly sharing their views on public matters for fear of harassment or persecution.”