Update on December 13, 2017: After 15 days of detention, poet Mustafa Sbeity was released on Tuesday, December 12, 2017, after paying a bail of 500000 L.L. (around $333), according to Annahar. However, the public prosecutor did not drop the charges against Sbeity and his case remains open.

On Monday, the Internal Security Forces’ Intelligence Unit arrested local poet Ahmad ‘Mustafa’ Sbeity for his Facebook musings about having relations with the Virgin Mary, sparking another round of challenges to free expression in Lebanon.

The 65-year-old Sbeity, who lives in Kfar Sir near Nabatieh, wrote on his Facebook page, “I am sad. Why has god not asked me to sleep with the Virgin Mary to give birth to Jesus Christ??!!” The post elicited a negative reaction; people shared screenshots of the post, claiming that it incited sectarianism. State Prosecutor, Judge Samir Hammoud, told the National News Agency that Sbeity was being detained on the basis of insulting the Virgin Mary and that he is being interrogated.

The 65-year-old Sbeity, who lives in Kfar Sir near Nabatieh, wrote on his Facebook page, “I am sad. Why has god not asked me to sleep with the Virgin Mary to give birth to Jesus Christ??!!” The post elicited a negative reaction; people shared screenshots of the post, claiming that it incited sectarianism. State Prosecutor, Judge Samir Hammoud, told the National News Agency that Sbeity was being detained on the basis of insulting the Virgin Mary and that he is being interrogated.

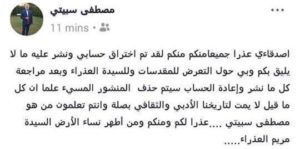

Responding to criticism, Sbeity initially wrote that his account had been hacked and that he did not have anything to do with the post. During the interrogation, however, he admitted to writing the post in a moment of “temper and drunkenness.”

Responding to criticism, Sbeity initially wrote that his account had been hacked and that he did not have anything to do with the post. During the interrogation, however, he admitted to writing the post in a moment of “temper and drunkenness.”

Several political news websites seized the opportunity to condemn the content of his post and urged the government to take action against him. The official website of the Lebanese Forces party featured an article with the accusatory headline “Mustafa Sbeity Offends the Virgin… and he is guilty until proven otherwise” and demanded immediate intervention from the authorities. Lebanon Debate, a website known for its sensationalism, called Sbeity’s post “disgusting” in a press release.

Selective amplification of social media posts and biased coverage has become a hallmark of Lebanese broadcast and online media reports on free expression cases over the past year and raise questions about the influence of such coverage on legal proceedings. Sbeity’s lawyer, Chawki Chreim, expressed concern that “judges become extra cautious about releasing the detainees when their cases are circulating on the media. I think that had the media and social media not been amplifying the case, they might have been able to release him after the investigation.” Chreim is also a representative of the Syndicate of Lawyers in Nabatieh.

Such media coverage may also lead the authorities to take disproportionate measures, such as imprisonment. According to George Ghali, executive director of ALEF, a Lebanese human rights organization that works on the prevention of arbitrary detention, “Sbeity should not be in detention because he does not pose a danger to the community.” After visiting Sbeity on Thursday, Lorca Sbeity, his daughter, told SMEX that, “The prison’s condition is very bad. There are 15 to 20 people in a small cell.”

The harassment and detention of social media users who have challenged religious and political norms is not new. Over the last 12 months, SMEX has recorded nine arrests of people in Lebanon who expressed critical opinions on social media. In 2014, the ISF arrested Ali Itawi in Dahieh for posting a picture of himself kissing a statue of the Virgin Mary. Itawi first posted the picture in 2011, but it only became controversial three years later, when he made the picture his Facebook cover photo. An uproar ensued in the media that prompted then-president Michel Suleiman to weigh in and encourage the authorities to do something.

Chreim informed SMEX that the Public Prosecutor’s office in Nabatieh detained Sbeity on the basis of articles 474 and 317 of the penal code. Article 474, which the authorities used to detain Itawi, stipulates that anyone who defames religious rituals or encourages the defamation of religious rituals should serve between six months and three years in prison. Article 317 pertains to sectarianism, sentencing those who encourage sectarianism in their writing, speeches or work to between one and three years in prison and a fine of between 100,000 and 800,000 L.L. (between $66.66 and $533.33). The news station MTV Lebanon has also speculated that Sbeity could be charged under Article 473 of the Penal Code, an anti-blasphemy article. Article 473 states: “whoever blasphemes the name of God publicly is punished with imprisonment from one month to one year.”

Such a prosecution would put Lebanon squarely out of step with global norms on religious speech. Ahmed Shaheed, the UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief, recently wrote that only 70 countries in the world have anti-blasphemy laws and 25 percent of them are in the Middle East and North Africa. He stresses that although governments often assert that anti-blasphemy laws prevent hate speech, these laws “are generally focused on the degree to which speech causes offence or outrage to religious sentiments, and not the extent to which that speech undermines the safety and equality of individuals holding those religious views.” In addition, rather than protecting religious minorities, they often “facilitate the persecution of members of religious minority groups, dissenters, atheists and non-theists,” Shaheed writes. Hasan Chami, vice president of the Secular Club at the American University of Beirut, agrees. The existence of Article 473 in this day and age is unacceptable, he says, warning that “vague terms used in such articles can be interpreted to prosecute people who express their personal views online.”

Perhaps Sbeity violated the Penal Code, but Article 474 has not been updated since 1954, and as an artefact of another time, it enables the Lebanese government to prosecute anyone who poses a challenge to prevailing religious and sectarian norms. Moreover, the use of Article 317 creates a dangerous environment for expression that effectively prevents people from one sect from using social media to critique, discuss, or challenge the religious practices and beliefs of people from another sect. Sbeity’s post clearly neither constitutes hate speech nor incites violence against Christians in Lebanon.

“Our problem in Lebanon,” said Chreim, “is that we want to mute the opinions that are not the same as ours and we want to destroy the people who hold those opinions regardless of their circumstances.”