Gaza has been through at least four near-total communication blackouts since October 7. The latest internet blackout, on November 16, was due to fuel shortage, backup batteries running out, and relentless bombing of telecom infrastructure.

Cutting off communications is a deliberate tactic by the Israeli occupation to ensure the outside world does not see the massacres it commits against Palestinians in Gaza. It is also a form of cyber-warfare, as information blackouts subject more people to danger, increasing casualties.

Without mobile networks and a stable connection to the internet, people are stranded with no way of calling emergency services such as ambulances and rescuers. They cannot update each other about where the bombs are falling and which areas to avoid. Those abroad often have to wait days before receiving a single message confirming their loved ones in Gaza made it through another Israeli raid.

Techies around the world have been trying to find alternative ways for Palestinians to communicate inside Gaza and with the outside world. One proposed solution is using eSIMs; but what are they? And are they safe?

What are the risks of eSIMs?

The challenges of using an eSIM are very similar to the regular SIM. This means that you have to be aware that the provider can know a lot about you, like the wider location through what antenna you are connected to, the device IMEI which is the physical identity of the device, the phone IP, the device model, among other identifiers.

In addition, a telecom provider who is an internet service provider for your mobile data can also dig into your data traffic to identify your internet usage and which apps you use. It can also track some of your applications’ metadata. This includes knowing when you go online on WhatsApp, who you call, and the call length.

This is why, if you must connect to a network you do not trust, it is crucial to use VPN while browsing the internet and using apps. Fortifying your digital security is even more critical in contexts like the war in Gaza, where you know malicious actors might want to harm you. You can also turn your device SIM network off (Airplane mode) when you are not using it. (Check the Gaza Media Resources website for more safety tips).

Embedded SIMs (eSIMs) are small chips integrated into networked devices (such as mobile phones) to securely store subscriber authentication details (ICCID, IMSI, authentication key (Ki), local area identity (LAI), and operator-specific emergency number, etc.). Unlike traditional physical SIM cards, eSIMs do not need to be inserted or removed from the device. They can be thought of as a virtual alternative to physical SIMs. The subscriber’s information is stored electronically, and the eSIM is reprogrammable, allowing users to switch carriers without changing physical cards.

Activating an eSIM involves downloading a carrier profile onto the device. This can be done by scanning a QR code, entering a code provided by the carrier, or using an app. These electronic chips (eSIMs) allow network operators (telecom service providers) to rewrite the stored information, but they are not designed for inter-device transfer.

It’s possible to transfer the subscriber profile associated with an eSIM from one device to another, provided that both devices support eSIM technology and are compatible with the same mobile network. This process is typically facilitated by the network operator and involves deactivating the eSIM on the original device and activating it on the new one.

This introduces novel risks, including the potential for malicious actors to seize control of mobile devices by manipulating a SIM’s identity information. It could also compromise the previous owner’s identity when disposing of the device, as the authentication data may still reside on the eSIM.

Some of the other risks associated with using eSIMS are profile spoofing and remote exploitation. Malicious entities can attempt to create fake or malicious eSIM profiles to trick devices into connecting to unauthorized networks. This could lead to unauthorized access to the device or interception of communications.

Since eSIMs can be remotely managed, attackers could exploit vulnerabilities in the remote management systems to gain unauthorized access, manipulate profiles, or disrupt service. Additionally, while eSIMs’ remote management capabilities make them more flexible, they could compromise privacy by allowing unauthorized access to their location, network usage patterns, or other sensitive information stored on the eSIM.

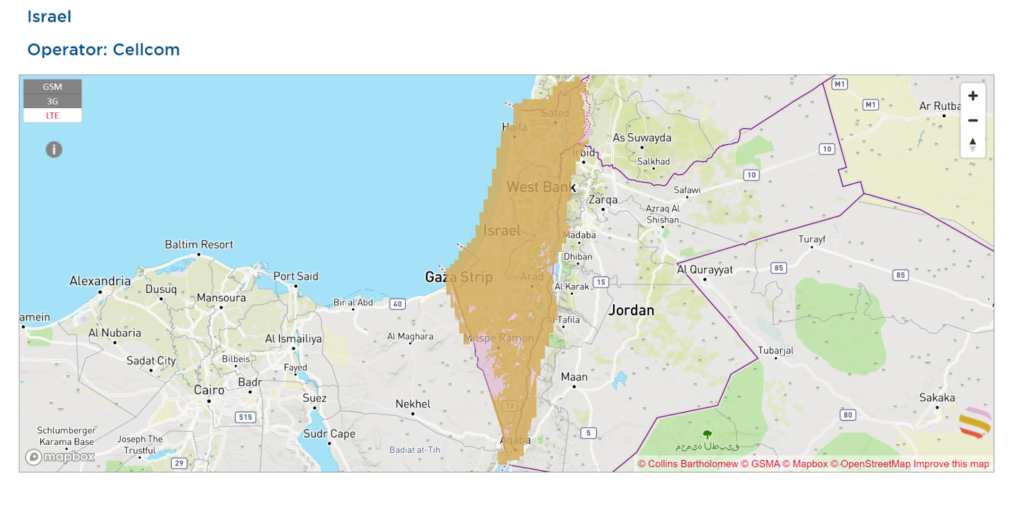

A device using an eSIM will scan neighboring networks to make a connection, but this requires being connected to the internet to begin with, which is a challenge under Gaza’s already crippled telecom infrastructure. Considering the Israeli occupation’s history of cyber-espionage and technology apartheid, it can potentially abuse and limit access to eSIMs if the device using the eSIM service is connecting to an Israeli telecom provider tower.

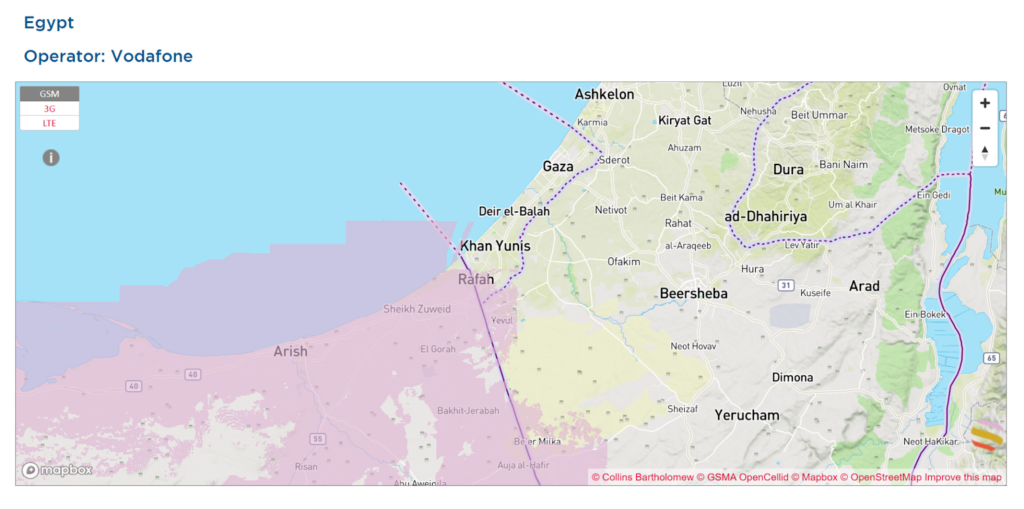

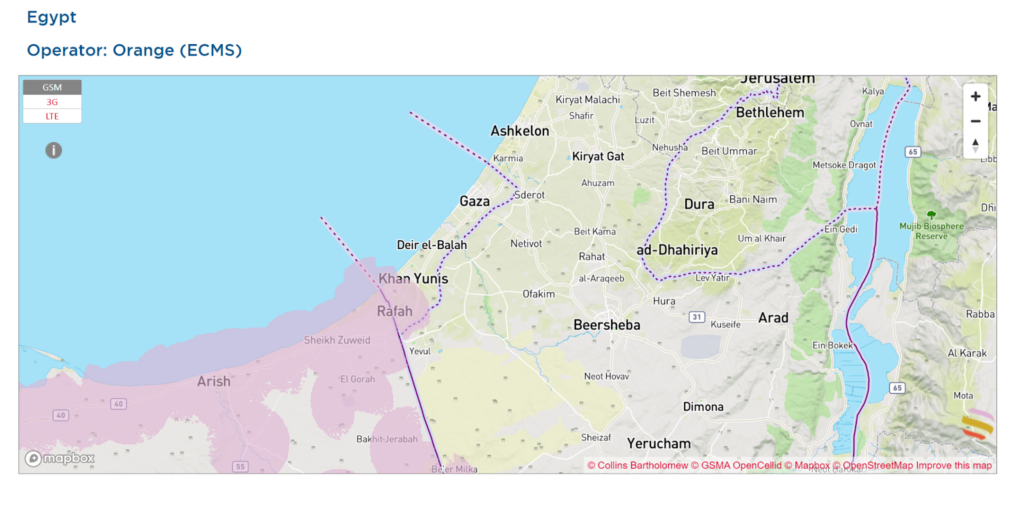

The second best option is connecting to an Egyptian network near the Rafah border, but those networks are reportedly weak and do not adequately extend to the strip. Many have reported that securing a signal is a real struggle. Another major drawback is that most eSIMs can only work on compatible or relatively new and expensive devices, such as an iPhone X or newer, which many people cannot afford in Gaza.

eSIMs became available in Gaza during this Israeli aggression thanks to the efforts of civil-led initiatives. Many individuals organized to buy thousands of eSIMs to be activated in the strip. All recipients had to do was scan a QR code and get connected to a supported cell tower. At first, the eSIMs were distributed to journalists and medical workers, but soon they became available to anyone.

Gaza’s telecom at the mercy of the occupation

The telecom infrastructure in the Gaza Strip was already compromised prior to the outbreak of the war. Internet connectivity is directly controlled by the Israeli infrastructure, in violation of the Oslo Accords, which grant Palestinians the right to run their independent ICT infrastructure.

Instead, the only fiber optic cable that connects it to the global internet runs through Israel. In addition, as part of its sixteen-year siege, the Israeli occupation prohibits the import of newer equipment to improve outdated technology, citing risks of “dual use.”

As the world develops the latest 5G technology, people in Gaza still use 2G networks. They mainly rely on fixed-line internet, such as local Wi-Fi networks, as the Israeli occupation authorities prohibit developing second-generation (2G) networks into third-generation (3G) networks in the strip.

While eSIMs provided a temporary solution for a limited number of people in Gaza, it remains largely unavailable for the majority of the strip’s population. It is reported that around 33,000 people out of 2.2 million could stay connected via eSIMs. eSIMs, no matter how important they’ve proved to be, remain an emergency alternative. The Israeli government must refrain from targeting telecommunications infrastructure and switching off the internet, no matter the circumstances. People should not be forced to seek alternatives to their right to stay connected.

In addition, electronic SIMs could pose real risks for people in Gaza, especially if they are connected to Israeli networks. An occupation that incessantly and indiscriminately bombs hospitals, schools, and shelters will have no moral restraint when it comes to hacking the devices of those it is trying to kill.

Beyond the immediate context of this Israeli aggression, Gazans must be allowed to rebuild and improve their telecommunications infrastructure, a right long-denied by Israel. Considering that the Israeli Army publicly declared its intentions to “bomb Gaza into the Stone Age,” concealing its crimes against humanity may be secondary to Israel’s aims of isolating Palestinians in the strip and inflicting maximum damage and terror wherever it can do so.