The 2022 FIFA World Cup brought Qatar journalists from all over the world, despite limitations to press freedom, such as the mandatory accreditation and restrictions to coverage outside stadiums. Although the Qatari government attempted to portray a polished image of the country to the world, many stories exposed a darker reality.

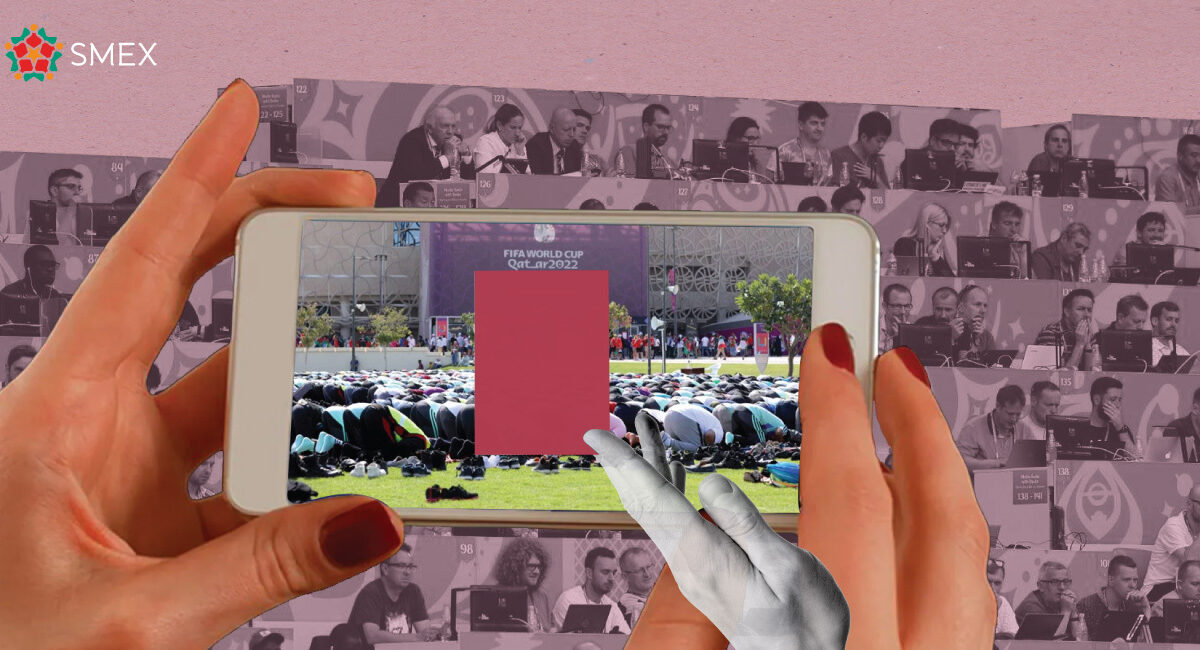

“I did not use my personal cell phone during my entire stay in Qatar, only my work phone,” explains Antía André, a Spanish journalist and special envoy for Radio Nacional to cover the World Cup in Qatar. “I was only deprived from filming once: Outside one of the stadiums where a line of men were praying. A member of security placed his hand in front of my camera and told me that it was not possible,” she added.

“We were asked not to use portable internet or satellite connection devices in press rooms and around areas of the stadium,” stated Joan Domenech, also a Spanish journalist from El Periódico. Journalists often use these tools to secure internet connection and send coverage to their offices. “They said it was to prevent signal interference, but I don’t know if it was to avoid uncontrolled communications.”

“However, the communications were excellent and in general terms, it was a very well-organized World Cup; the best of the five I have been to, with a lot of facilities and money invested. Even to the point of obscene opulence,” he added.

A restrictive and arbitrary press accreditation

Covering the World Cup in Qatar differed to documenting past tournaments in other countries. In addition to the privacy risks posed by the Hayya app, every journalist or news organization had to acquire a press accreditation whose terms restrict press freedom. By accepting these terms, journalists were not allowed to film or photograph “residential properties, private businesses and industrial zones.” It also entailed accepting some vague restrictions, such as “respecting the privacy of individuals” or “complying with Qatari laws.”

“World Cup coverage is not limited to what takes place on the field. What’s happening in the stands and in the city, the atmosphere, and the context are also covered. All this implies a freedom that many journalists fear they will be denied in Qatar,” stated Reporters Without Borders.

“Since the beginning of the World Cup, we have witnessed a number of incidents against the press including reports on journalists being briefly detained, prevented from filming, or having their equipment seized. These are clear acts of intimidation,” says Pamela Morinière, Head of the International Federation of Journalists’ (IFJ) Communications and Campaigns department.

Among these incidents that IFJ pointed out, many are related to support for LGBTIQ+. For example, U.S. freelance journalist Grant Wahl, who suddenly died during the World Cup, was briefly detained for wearing a rainbow t-shirt to Ahmad bin Ali Stadium. Victor Pereira, a Brazilian journalist, was harassed by the police because they mistook the flag of Pernambuco for the pride flag.

Another highly controversial issue is the prohibition of filming private properties in a country where distinguishing between public and private spaces is not easy.

A hotbed of surveillance against journalists

“The problem with the accreditation process is that the restrictions are so broad that it functionally limits journalists working to a tiny swath of the country,” explained Justin Shilad, Committee to Protect Journalists Senior Researcher of the Middle East and North Africa. “Additionally, these categories are very general and what constitutes trespassing on private property, for example, is often decided at the moment,” he added.

“In Qatar, the line between public and private property is almost impossible to distinguish. In some sense, everything is government property,” protested Craig LaMay, director of the journalism and strategic communications program at Northwestern University in Qatar, to SMEX.

Along these lines, many of the incidents mentioned by the IFJ during the coverage of the World Cup have to do with this distinction between public and private property, a recurring problem among Qatari journalists. For example, on 15 November, security officials interrupted a live broadcast from a Danish TV2 team in a public space in Doha. The same happened to Joaquín Alvarez, Argentinian, and his crew, who were prevented from live broadcasting in Barwa Village, a commercial and residential complex on the outskirts of Doha. Another incident took place with Duch Bas Scharwachter, a reporter for NU.nl, who was forced to delete photos of security guards outside the Al Thumama Stadium during the inauguration of the tournament.

An investigation by The Bureau of Investigative Journalism and The Sunday Times revealed that Qatar hired hackers to intercept email accounts and other private communications of journalists critical of Qatar. This is a severe violation of press freedom and digital protection for journalists and their sources. IFJ published seven recommendations to support journalists’ safety while reporting on the ground. These included securing contacts with embassies or consulates and how to backup sensitive material, especially if journalists suspect they might be subjected to surveillance under the Hayya app or the Covid-tracking app Ehteraz.

“We have witnessed numerous examples of hacking in the past years,” stated Justin Shilad, from the CPJ. “Journalists’ ability to protect their sources underpins the operation of a free press and any attempt to challenge this protection seriously undermines the vital work of journalists to hold the rich and powerful to account.” These limitations have not been only imposed now for the World Cup, but reflect a history of limiting the freedoms of journalists in Qatar.

Qatar, a Not-free country

According to the 2022 World Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders, Qatar is considered non-free, and falls at the end of the list at position 119 out of 180. However, as of today, no journalist has been murdered or imprisoned for doing their job, which, far from evidencing a good situation in terms of press freedom, shows that a very high degree of self-censorship is exercised in the country.

“Journalists generally have to practice a strong degree of self-censorship because they are subject to surveillance and spyware risks, and have very limited opportunity to pursue critical coverage of domestic issues,” said Justin Shilad from CPJ. “In general, and with Qatar specifically, CPJ has serious concerns about the use of spyware and surveillance technology against journalists and the compromising of their personal accounts. The risks to journalists and the threat to press freedom are grave,” he added.

Various legislation, including the 1979 Press and Publications Law, the 2014 Cybercrimes Law, and the 2020 Penal Code amendment, criminalize the spread of “rumors” or “false news” by issuing heavy fines and jail terms. “The legislation does not define what is considered a rumor or fake news, which gives unacceptable room for interpretation,” added Pamela Morinière from IFJ. “It is used as a deterrent that forces journalists to self-censor.”

As Craig LaMay who has been teaching journalism for 14 years pointed out, Qatar’s ranking as unfree is pretty well deserved and Qatar’s media laws, far from getting better with years, have gotten even worse: “If you are a journalist or if you publish a story that talks about the government, you are obliged to get a response from the government communications office and if you don’t get it, you’re not supposed to publish. If you do, they can tell you to take it down.”

As such, journalists decide not to speak about an issue to avoid conflict with the authorities. “For example, many of my students have long wanted to cover stories on LGBTQ issues, but that is indeed a hot-button issue. If they did, we’d get in trouble for it. So, yeah, I have personally told students, ‘no, you cannot publish that story,’” he added.

Sports as a means to whitewash human rights violations

All this context questions the choice of Qatar as the venue for the FIFA World Cup. “Qatar’s election should not have been politically motivated, but it was decided by elites who cared little about human rights. Nor should it have been granted the 1982 World Cup in Spain or in 1978 in Argentina, when two military dictatorships were in force,” said the Spanish journalist Joan Doménech.

“With the Winter Olympics in Beijing, the Spanish Super Cup in Saudi Arabia and the World Cup in Qatar, it is time for the media and journalists to reflect on how to cover events in countries where their colleagues are in prison, whipped or mistreated,” added Alfonso Bauluz, Head of RSF in Spain.

FIFA, as a global entity with the capacity to influence the masses, should promote values that respect and protect human rights, instead of supporting countries like Qatar and others that violate fundamental rights. “If FIFA wants to be a serious force for good in the world and contribute to an improvement in human rights and press freedom in Qatar and globally, they should consult with local civil society in potential host countries and make a commitment to improving a country’s rights record when considering who hosts global tournaments,” added Justin Shilad.

“If someone is worried that you are critical of their government, it is because they have something to hide,” said Spanish journalist Antía André. “We cannot trust what we have read and have not seen, but neither what we have seen during this World Cup, because I believe that this is not the reality,” she added.

Although the World Cup has whitewashed the reality of Qatar by welcoming fans and journalists from all over the world, the global event also drew attention to the country’s human rights violations. It made it possible to denounce situations that were previously invisible to the world, such as the mistreatment of the migrant population.

Now, the biggest question is the future. Will another country with a record of violating human rights become the next host of a mega-sporting event? What will happen to coverage of humanitarian events in Qatar once media attention fizzles and fades?