On August 24, 2021, the technology community in Lebanon woke up to the alarming news of a “digital disaster,” announcing that thousands of Lebanese websites belonging to organizations, universities, and institutions will be lost. Websites that end in (.lb), Lebanon’s internet country code top-level domain (ccTLD), now have to pay a fee to the entity in charge of registering and managing the (.lb) domains, namely the “Lebanese Domain Registry” (LBDR), run by Nabil Bukhalid.

Previously, the registration of domains ending with (.lb) was free of charge, since the American University of Beirut (AUB) used to host and support the infrastructure for the “Lebanese Domain Registry” pro bono. Now that the university has discarded the two employees who used to run the registry, what will be the fate of (.lb) domains?

Who Is Responsible?

In an interview with SMEX, founder of LBDR Nabil Bukhalid explains that AUBt “was not managing the domain registration process, but provided the infrastructure as well as logistic and financial contributions, by allowing employees in the department to dedicate part of their time to the registry.”

“When I quit my job at AUB in 2012, the university asked us to transfer the registry, so I established the “Lebanese Internet Center” (LINC) as a semi-public and semi-private organization with stakeholders from the public and private sectors, to manage top-level domains (.lb ccTLD and .Lebanon),” stated Bukhalid. “However, the organization did not obtain approval from the Lebanese Ministry of Interior. As a result, AUB continued to host the registry until 2020, when the university dismissed the two employees who were operating it.”

Those interviewed by SMEX complained that they were not familiar with the “Lebanese Domain Registry” company, which is registered in Delaware, USA and manages Lebanese domains from abroad. According to Bukhalid, the decision to register the company in the US came about “after extensive research on the best host countries.” He discovered that the law in the state of Delaware protects data and does not impose taxes on domain registries.

He also gave his reasons for not hosting the registry in Lebanon. For example, the association he founded to manage the domain registry did not receive a certificate of good standing from the Lebanese Ministry of Interior. When AUB announced that it would no longer host the infrastructure of the Lebanese Domain Registry in the summer of 2020, Lebanon was going through a major protracted economic crisis. “We were unable to open any new bank accounts in the country or even transfer any funds abroad to pay the server’s operating costs,” said Bukhalid. He confirmed that he was personally authorized “by virtue of government decree to continue managing the operations of the Lebanese (.lb) domain registry in October 2020, after several parties refused to take charge of the registry, including Ogero.”

Editorial Note: After publishing this article in Arabic, Ogero denied that it refused to take charge of managing (.lb) domains, stating that: “Ogero was seeking to assume this responsibility and did not reject it at all.” SMEX is only concerned with providing insight into the (.lb) domains issue, acknowledging that there might be contradictory viewpoints to the situation.

Nonetheless, registration in the United States may involve “legal challenges,” according to Mohamad Najem, the Executive Director at SMEX.

Najem explained that “compliance with US laws can affect, for example, removing content or freezing domains belonging to what it considers banned entities.” On the other hand, he expressed his understanding of what the company has done, “especially in light of AUB’s decision and the crises at the level of privacy and data protection in Lebanon.”

Will (.lb) Domains Stop Working Permanently?

“There’s nothing to worry about,” reassured Bukhalid. “After all, domains are like a yellow pages directory, where we put the domain on hundreds of servers around the world so that browsers can access it.”

As for government domains (.gov.lb.), Bukhalid reiterated: “We have nothing to do with them. They are managed by the Office of the Minister of State for Administrative Reform (OMSAR), which has the right to access our system to renew and verify domains upon request from the State.” On the other hand, he explained that universities and associations “are the ones who pay the cost of registering their own domain, and they have not faced any problems.”

As for security concerns, Bukhalid revealed that LBDR’s domain server is located in New Zealand, which provides greater data protection. “Using a cloud server saves a lot of costs, which are divided between subscribers,” explained Boukhalid, adding that cloud technology provides data centers all over the world. “We cannot afford it on our own. It is also not feasible to establish a data center in Lebanon due to the high cost, as well as the poor electricity and internet infrastructure in the country.”

Confusion in Reactivating the Domains

The Lebanese Domain Registry, established towards the end of 2020, began notifying owners of (.lb) domains about the process of transferring domain management from AUB to domain-management entities.

According to the company’s website, a total of 4,552 domains have made the transition from registry-centric to registry-registrar operation mode as of February 2021. 4,314 websites are now active, while 380 have been suspended but can be reactivated by renewing the registration.

This domain registration renewal process does not take place through the Lebanese Domain Registry, explained Bukhalid, but through local “registrars,” namely Abu-Ghazaleh Intellectual Property, IDM, PracticalHost, SODETEL, and Terranet.

However, the process of renewing domains in the registry has not been easy for everyone. Shakib Al-Jabri, an information security specialist who had registered several websites on the (.lb) domain, told SMEX that on May 30, he found a message from the Lebanese Domain Registry in his spam warning him that he had “until July 30 to make the domain transfer, without providing any explanation as to why.”

Al-Jabri then informed the (.lb) domain owners and renewed the domain for someone he was still in contact with, before receiving a renewal confirmation email from the Lebanese Domain Registry on June 30. As for the registrars, who operate the domains for a fee, “none of them responded to our emails,” said Al-Jabri. He explained that out of all the companies he had contacted, Talal Abu-Ghazaleh Intellectual Property was the only one that responded swiftly.

After struggling to get a hold of these companies over the phone, Al-Jabri was finally able to contact SODETEL. He paid 40 US dollars to keep the domain for another year, noting that the dollar rate in the black market these days is about 19,000 Lebanese pounds (the official rate lbp1,500 for $1).

In this context, Bukhalid confirmed that the sum the Lebanese Domain Registry charges for including (.lb) domains in the registry and operating them amounts to $20. “We do not charge domain owners. We charge registrars who we chose as our registered companies in Lebanon. They are the ones who carry out the renewal process for the domains, and each sets the suitable price,” he said.

Not Enough Time

“Messages sent to contacts were not enough,” said Data Management and Analysis Consultant Naji El Kotob, who used to run a domain registration company. “Years ago, the person who used to register the domains was often the IT in the company or a company providing domain registration services. That person may have left the company a long time ago or the service provider has closed its doors, and they simply did not communicate that to the concerned parties.”

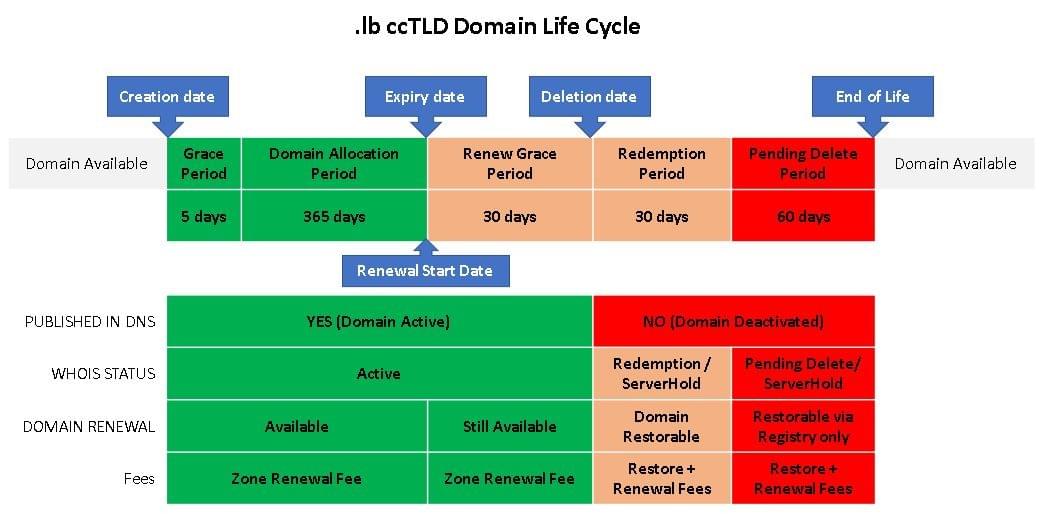

El Kotob finds that the grace period, which ranges between 30 and 60 days, is insufficient, especially considering the difficulty reaching domain owners who are now impossible to track. “Sometimes, when a domain’s registration is 15 or 20 years old, finding the right contact can be difficult because search engines prioritize the domains in Lebanon,” said Kotob. He added that several domain owners opted out of (.lb) domains following the confusion that happened and its impact on their business.

In response, Bukhalid said that his company sent notifications to domain owners as soon as they started operating in early 2021. He explained that the domain life cycle is available on the company’s website in the Policies section, Appendix C. (See figure below).

Bukhalid told SMEX that he notified domain owners about renewing their subscription so he could secure the money to transfer the domain’s registry to servers abroad, otherwise the domains would stop working entirely.

Upon the expiry of the 30-day limit, the domain owner is given an additional 30 days. If they do not respond, their domain enters the redemption period for another 30 days. After 60 days, the domain is frozen, and only the domain owner can renew it by submitting a request in their name. “Registrars can also sign a document stating that they have renewed the domain on behalf of its original owner,” Bukhalid added.

As for domains registered under “businesses” at the Ministry of Economy before the promulgation of Law No. 81/2018 on “Electronic Transactions and Personal Data,” these remain active for a period of 365 days.

The “Electronic Transactions and Personal Data” law recognizes, in its third and fourth chapters, that the “Lebanese Accreditation Council” (COLIBAC), established by virtue of Law No. 572/2004, is responsible for “accrediting authentication service providers who issue certificates to electronic writings and signatures provided they meet the requirements,” and that it “determines the conditions and obligations in the protection measures provided by authentication service providers.”

However, this Council remains a non-active entity that is unable to play the role that accreditation bodies in Europe and all over the world assume in conformity assessment. The Council is also unable to carry out specific tasks under the relevant Lebanese laws regarding the activities of the National Accreditation Authority or conformity assessment due to the delay in appointing a general manager and staff for the Council, according to the Lebanese Ministry of Economy.

Each time the State absolves itself of its responsibilities, and the private sector falls short when trying to compensate for the damage, internet users fall victim to the ensuing inconsistencies.