So far in this series, we’ve given brief overviews of the history of Western legal frameworks in the Arab region and looked at constitutional frameworks and how they interact with both national legal systems and international law. The aim is to set the stage for Part II of the series, which will begin next week and focus on current legal trends restricting free expression online and other digital rights. But first, we need to examine a lesser-known facet of rights frameworks, regional systems.

The European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, France. By Eugene Regis on Flickr: https://flic.kr/p/3bQ86E.

While regional systems of governance on human rights may come into play less frequently than national and international laws, particularly in the Arab region, where a regional human rights charter only came into force six years ago, they are important to consider for a couple of reasons. First, examining compliance with human rights instruments through a regional lens will expose both new threats and opportunities. If States are cooperating at a regional level on issues like cybercrime, for example, knowledge of that cooperation may provide leverage for intervention.

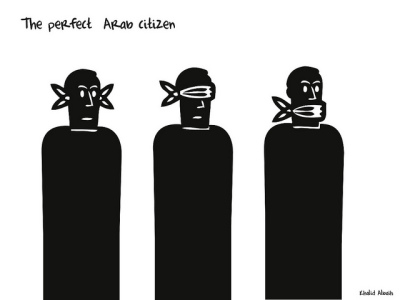

Second, adopting a regional outlook creates an opportunity for comparison and helps dispel myths of exceptionalism, specifically the idea that shared cultural and religious mores of the Arab region exempt it from protecting and respecting universally acknowledged human rights. Observing how diverse regional assemblies, such as the Organization of American States (Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, 1959), the Council of Europe (European Court of Human Rights, 1953), and the African Union (African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, 1987), have adopted and enforced human rights charters through regional courts offers instructive examples for the analogous Arab assembly, the League of Arab States, which to its credit though with significant missteps, has only recently begun to follow suit.

The Arab League Acknowledges Human Rights

Since the formation of the League of Arab States (LAS)[ref]The members are: Algeria, Bahrain, Comoros, Djibouti, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, united Arab Emirates, and Yemen. Syria’s membership was suspended in 2011.[/ref] in 1945, members have cooperated on a range of issues. The internet and human rights are no different.

In October, for example, the 22 states submitted “common proposals” at the ITU plenipotentiary asserting that the formulation of Internet policy is “the sovereign right of states.” Countries have also coordinated on the Arab Convention on Combating Information Technology Offenses.

Unlike its regional counterparts, however, the 22 members of the LAS are not accountable to each other via a higher collective regional authority. Decisions are made by unanimous vote and members’ cooperation is voluntary.[ref]http://www.icnl.org/research/monitor/las.html[/ref]

With its purpose of “mainly regulating relations between States,” the founding Pact of the LAS “makes no reference to human rights nor to any direct representation of Arab citizens.”[ref]“The Arab League and Human Rights: Challenges Ahead,” FIDH p. 10, May 2013.[/ref] It wasn’t until 1960 that an Arab convention on human rights was requested—by the Union of Arab Lawyers—and it took 34 years for the first version of the Arab Charter on Human Rights to be adopted. This charter largely resembled other international and regional human rights instruments, with regard to rights guaranteed, but it expired, before being ratified by the required seven states.[ref]http://www.icnl.org/research/monitor/las.html[/ref]

Remember! Today, December 10, is Human Rights Day. Help us express our solidarity with our friends Alaa Abd El Fattah and Bassel Khartabil and many others, currently serving arbitrary prison sentences in Egypt and Syria for breaking the silence of oppression by expressing their thoughts, asking questions, and thinking critically and constructively about how to solve the problems before them. #FreeAlaa #FreeBassel

Until the second charter was drafted in 2004, the 1996 Sana’a Declaration on Promoting Independent and Pluralistic Arab Media was the only international document affirming a regional commitment to the right to media freedom.[ref]In a remarkably frank, if indirect, acknowledgment of the habitual abuse of free expression by Arab governments, the declaration calls for adherence to a predictable legal framework that respects this and related rights, stating: “Arab States should provide, and reinforce where they exist, constitutional and legal guarantees of freedom of expression and of press freedom and should abolish those laws and measures that limit the freedom of the press; government tendencies to draw limits/ “red lines” outside the purview of the law restrict these freedoms and are unacceptable.”[/ref]

In 2008 a long-awaited Arab Human Rights Charter came into force. To date, seventeen countries have signed the charter; 13 have ratified it.[ref]http://www.icnl.org/research/monitor/las.html[/ref]

Article 30 of the charter guarantees “the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion, which may be subject only to such limitations as are prescribed by law.” Article 32(1) affirms “the right to information and to freedom of opinion and expression, as well as the right to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any medium, regardless of geographical boundaries.” Article 32(2) articulates possible “limitations as are required to ensure respect for the rights or reputation of others or the protection of national security, public order and public health or morals.”

Unfortunately, the nearly 50 years it took to get the charter hasn’t made it meaningful. While the charter establishes a treaty body[ref]This committee is referred to as both the Permanent Human Rights Committee and the Standing Committee on Human Rights.[/ref]—a traditionally independent committee charged with monitoring States’ compliance with the treaty—its members'[ref]Committee members’ independence is qualified by three factors. First, they must be from member states. Second, their recommendations must be supported by two member states. Third, only accredited NGOs (most of whom have ties with their governments) can gain observer status and submit official documentation for the reports. ICNL and FIDH report. Moreover, reviews didn’t begin until 2012, a full four years after the treaty went into force, and to date remarks have been made available in Arabic only.“The Arab League and Human Rights: Challenges Ahead,” FIDH p. 15, May 2013.[/ref] mandate is simply to “study in public” reports submitted by the States parties “on the measures they have taken to give effect to the rights and freedoms recognized in this Charter and on the progress made towards the enjoyment thereof.”[ref]Translation by Al-Midani, Mohammed Amin and Mathilde Cabanettes. Revised by Professor Susan M. Akram. “Arab Charter on Human Rights 2004.” Boston University International Law Journal, Volume 24:147. 2006 pp.147–164.[/ref] In other words, committee members can only consider information submitted by the states themselves.

Courting Disaster?

What has undermined the charter most, however, was that it didn’t establish an enforcement mechanism, such as the human rights courts present in other regional systems.[ref]Ibid, and “The Arab League and Human Rights: Challenges Ahead,” FIDH p. 17, May 2013.[/ref] In 2011, the Kingdom of Bahrain proposed setting up such a court, inspiring both some satire (given its own repression of free speech and protests that year) and an LAS decision to study the idea.

In the interim years, however, plans for the court have not lived up to the promises of the Charter or citizens’ expectations, as 27 human rights organizations expressed in recommendations for amendments to the statute in June. Chief among the recommendations is to amend the statute to allow citizens to bring cases directly to the court, without sponsorship of their home State, a requirement that international and regional human rights organizations charge“ defeats the very purpose and objective of establishing this Court.” Incidentally, that same month the League committed to developing a regional human rights strategy at a conference hosted by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Disappointingly, on September 7, 2014, despite the calls and commitments to grand strategies, the statute establishing the court was adopted by the League’s Council of Ministers without any of the recommended changes. The International Commission of Jurists called the move “an empty gesture that will do nothing for the victims of human rights violations” in the region. More likely, it seems, the presence of the court and its operation by the regimes responsible for rights violations will simply reinforce current practices and consolidate States’ power, rather than act as the check that is so badly needed.