Across history, we’ve observed how gender bias in STEM fields is mirrored in outcomes lacking precise data on women. For example, according to “Verity Now,” a US-based campaigning group striving to achieve equity in vehicle safety, women are 73% more likely to be injured than men because car safety tests are carried out on a male mannequin.

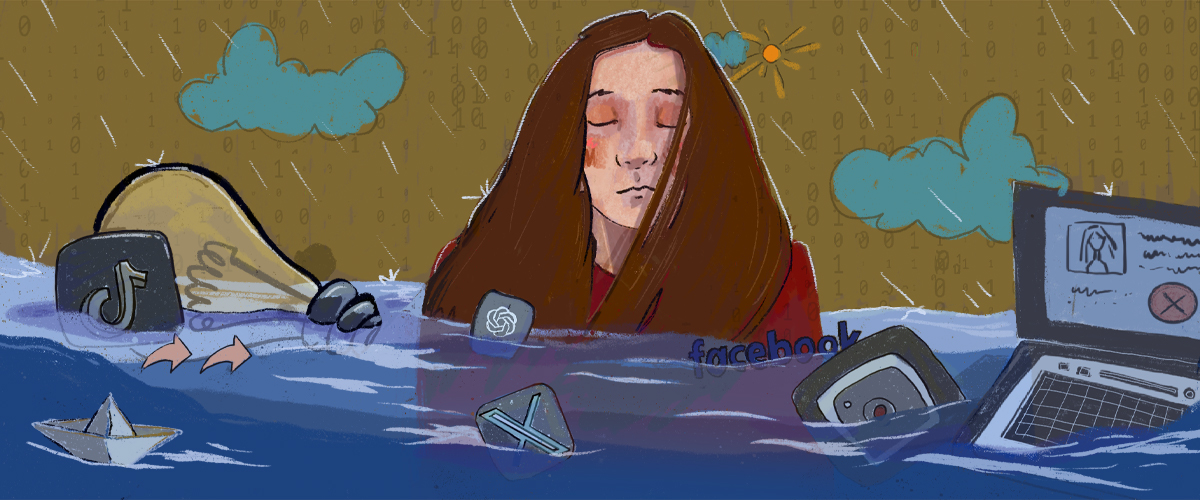

Since data is at the core of technology, the gender gap in this data is also being mirrored in technology. The Global Gender Gap Report 2018 warned about the possible emergence of new gender gaps in advanced technologies, such as the risks associated with emerging gender gaps in Artificial Intelligence.

According to statistics by the “World Economic Forum” in the Global Gender Gap that benchmarks the current state and evolution of gender parity across four key dimensions (Economic Participation and Opportunity, Educational Attainment, Health and Survival, and Political Empowerment), Lebanon’s global gender gap ranked 136 out of 149 countries in economic participation and opportunity in 2018, reminding us that Lebanon still lags on matters of gender equality.

Regarding educational attainment, the gender parity index of the proportion of girls and boys enrolled in school in Lebanon as of 2020 indicates the number of girls in primary school was equal to that of boys, as in the previous year. The ratio slightly favored girls in the lower secondary level while in the upper secondary levels, the number of girls was slightly lower than that of boys. This indicates that women have relatively equal access to education. Globally, men outperform women in math, yet girls and boys in Lebanon perform equally as well in secondary school math, according to The Arab Gender Gap Report 2020.

However, Lebanon has fluctuating performance and participation rates for women in STEM. The average enrollment for women in sciences across Lebanese universities was around 54% in 2018, although only 25% of women pursue degrees in engineering. In addition, university engineering cohorts across Lebanon have witnessed a “trickling out of STEM” phenomenon: women obtain higher education degrees in STEM but transition into more socially acceptable, non-STEM careers, such as education services.

The fluctuation of women’s participation in STEM fields in Lebanon results from the heavy influence of social norms imposed by parents and male peers, according to the report published in 2017 by USAID. Many male and female students and faculty mentioned the pressures of societal norms affecting student majors and career choices.

In Lebanon, parents highly value education for their children and view it as an important tool, particularly for girls, to have an independent future. However, according to the USAID report, parents play a critical role in imparting cultural norms that affect their sons’ and daughters‘ major and career choices (see table below).

Overall, female students discussed how parents encourage daughters to major in or follow stereotypical female programs and careers, such as humanities, social sciences, and health specializations. Similarly, male students mentioned that parents encourage them to major in or follow stereotypical male programs and careers such as applied science such as engineering, electronics, and economics, even though young women reported interest in virtually all career fields, from medicine and education to skilled labor and the armed forces.

When it comes to male peers’ influence, the report also highlights that both male and female students mentioned how some students and members of society perceive a woman‘s main role in the family to be a homemaker, caregiver, and mother, and the man‘s main role in the family as the leader and breadwinner, which is also reflected in the work field.

Our team interviewed three different Lebanese women working in tech fields in Lebanon. Each and every woman highlighted social norms as one of the biggest obstacles in their fields.

Dana Shimaly, who leads the development team at Stitches Studios for web development and 3D modeling, highlighted that her main pressure at work results not from her role as a team leader but from the fact that her team consisted of five men who underestimated her adequacy in leading them in development. Her perspectives and input were always questioned, contrary to other male leadership skills in the team. In addition, the team often described her as “bossy,” in comparison to the other male leader being “assertive.”

Inas AlHafi, an educational technology consultant and a trainer in digital literacy and programming, told SMEX: “Nowadays, the situation of women working in tech has become more acceptable than before. However, challenges and stereotypes still exist, and the perception of women in tech is influenced by cultural norms and traditional gender roles, especially when it comes to high positions and leadership of conferences and events traditionally held by men only.”

Both Dana and Inas highlighted the role of society in affecting women’s choices. They stated that tech fields are perceived as highly technical and require a high level of intelligence that society does not believe women are capable of managing, adding that it’s essential to note that attitudes and perceptions can change over time, and the efforts to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion in the workplace can contribute to positive shifts in how women are perceived in tech. Feminism here plays a major role in the efforts invested into this shift.

While the region is still a long way from reducing the gender gap in technology, some women are taking matters into their own hands to expedite change and counter widespread misconceptions. We are witnessing this through the growing number of women in the MENA’s tech ecosystem. In an article on the start-up environment, May El Habachi stated that about 34% of entrepreneurs are women; a rate which is believed to be much higher than in Silicon Valley, according to the UN World Tourism Organization (UNWTO).

In Saudi Arabia alone, participation of women in tech reached 28% in Q3 2021, significantly surpassing the European average rate of 17.5% during the same period, according to Endeavor Insight. However, women in tech are still underrepresented in the Middle East. They make up 24.6% of the workforce, one of the lowest in the world, according to a recent report by McKinsey.

Finally, as we stand at the crossroads of the present and the future, it is evident that technology will continue to play an ever-expanding role in changing not only how we live but also the landscape of the world we will soon occupy. It highlights how human skills are increasingly important and complementary to technology, and in an effort to ensure the development of technology that addresses the needs of all, the world cannot afford to deprive itself of women’s talent in sectors in which talent is already scarce.