Written by Riyadh Al Balushi @RiyadhBalushi

The World Intellectual Property Day, an event organised by the World Intellectual Property Organization, is held on April 26 of every year to “celebrate innovation and creativity.” The rights granted by intellectual property laws, such as copyright, are meant to draw a balance between the rights of creators to make a living out of their craft, and the rights of members of society to have fair access to these cultural works. One of the ways in which this balance is achieved is by making copyright law last for a temporary period of time and not forever.

When the term of copyright protection expires, the work enters the public domain. Works in the public domain can be copied, shared, and translated by any person for free and without the need to seek anyone’s permission. It is very important for us to have access to freely available public domain works because they make up many of the building blocks that we use to create new cultural and scientific works.

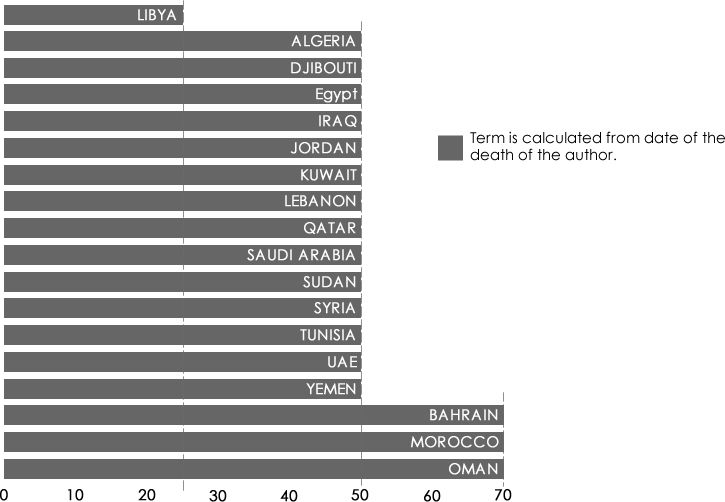

Figuring out how when this term expires can be a difficult task because it differs from one country to the next and varies depending on the work in question. For example, books and other literary works are protected in the Arab World from the moment the work is created for the entire lifetime of the author plus 25, 50, or 70 years after his death.

The majority of Arab countries protect books for the lifetime of the author plus 50 years after his death as a result of their international obligations under the TRIPS and the Berne Convention. Bahrain, Morocco, and Oman provide a longer copyright term than the rest as a result of their signature of a free trade agreement with the United States, not too different from the infamous TPP currently in the works.

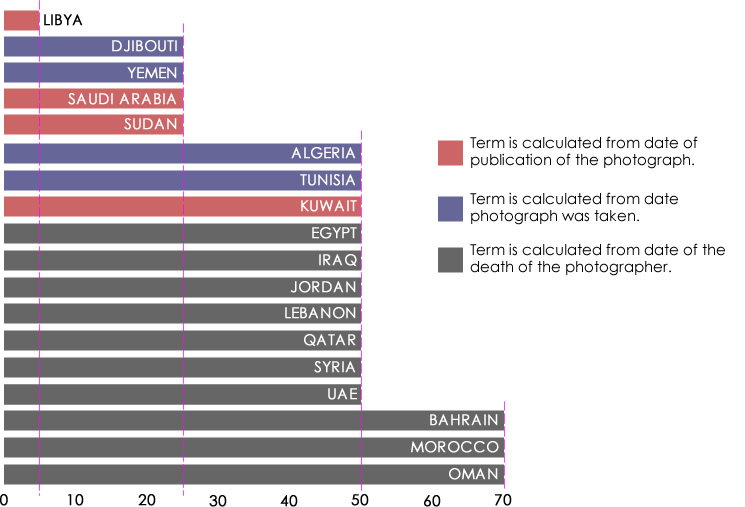

The term could be more complicated for different kinds of works. For example, even though the majority of Arab countries protect photographs for the same duration as books, some countries provide a shorter term of protection for photographs that is calculated from the moment the photograph is taken or published.

The charts above show that calculating copyright term is complicated. For example, “Afghan Girl” by Steve McCurry was taken in 1984 and published in National Geographic in 1985. The photo has been in the pubic domain in Libya since 1991, in Saudi since 2010, in Yemen since 2011, and remains protected by copyright in all countries where the term is linked to the lifetime of the author because Steve McCurry is still alive.

Should countries that have a shorter term make everyone’s life easier and extent their protection to match those that protect copyright for the longest period? The argument often presented by those who support a longer copyright term is that the author of the work spent time and effort to give birth to his work and therefore deserves to have his work protected in a manner that makes it possible for him to make the profit he deserves, which should consequently encourage him to create more works.

The argument against extending copyright terms is that there is no evidence that authors would feel more incentivised to create new works if copyright granted protection for their work for 70 years instead of 50 after their death. On the contrary, users in countries such as Bahrain, Morocco, and Oman are clearly disadvantaged by the longer term because they have to wait for 20 years longer than their Arab neighbours before universities, students, and other users can legally copy, translate, and use old works. This 20 years difference can easily make sectors that rely on copyright, such as the education and entertainment industry, more expensive to operate than their neighbours.

This is not to say that things are perfect in countries where the protection lasts for the lifetime of the author plus only 50 years, this duration is already too long and practically means that works created by others during our lifetime is not likely to join the public domain except after we die. Copyright laws in the Arab world provide exceptions that allow users in certain circumstances to copy and utilise works without the permission of the author, but no Arab country has a “fair use” exception and the existing exceptions are limited and do not satisfy the needs of the users of creative works on the internet.

Arab countries should not extend the length of their copyright term without thinking of the consequences that this will have on the ability of society to access knowledge and culture. Additional protection does not necessarily mean a greater incentive for authors to create and certainly does not create a better copyright system.

This article was written jointly by Riyadh Al Balushi and Sadeek Hasna and originally published on Global Voices Online on the 27th April 2015. Charts are taken from the Infographic on Copyright Term in the Arab World.