With the click of a button, you can become a character in the Marvel universe, get transported to the surface of Mars, or reappear in any video—thanks to the many artificial intelligence (AI) applications becoming more widely available to the public. But at what cost?

Many AI-based applications have been made public to further test their capabilities in text generation, image modification, and writing programming codes. Popular applications such as WOMBO.ai, Hotpot.ai, and Lensa allow users to modify images and videos using AI, enabling people to merge their personal photos with tailored backgrounds, bodies, or features.

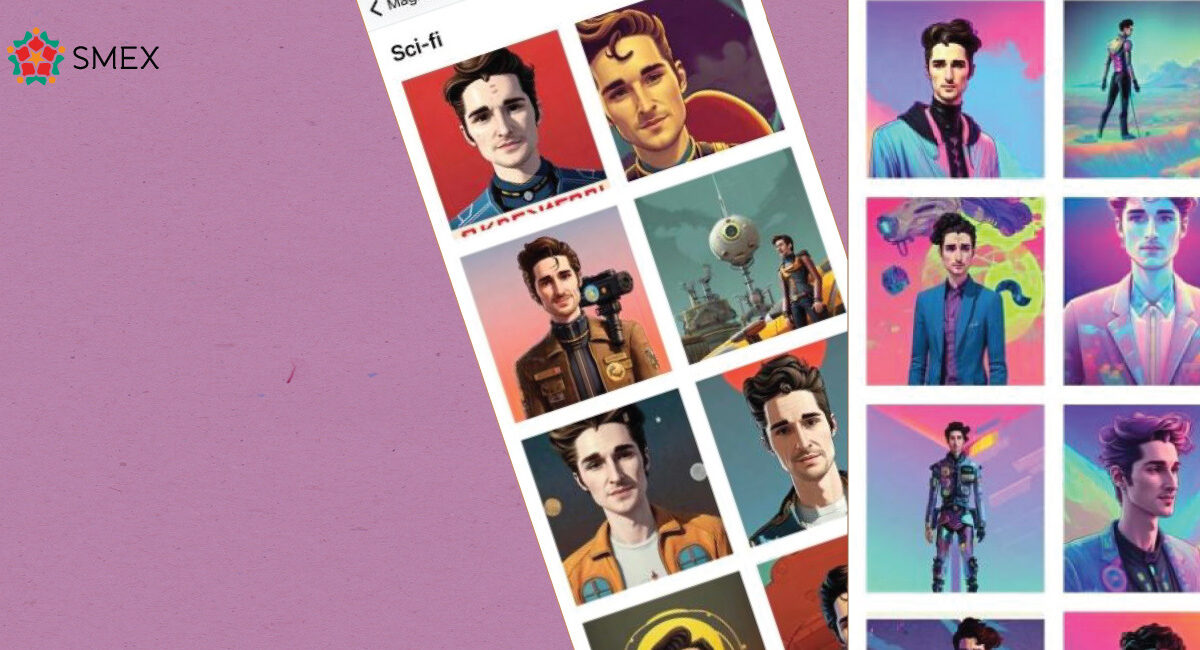

One of the most prominent of these applications is Lensa, an app developed by California-based The Prisma Lab and made available for download on Google Play and the App Store. Lensa allows users to upload their photos and use AI tools to turn them into digital artworks inspired by various themes, such as science fiction, space, pop culture, and many others.

(Not So) Free Service

The app gives users the option to subscribe for $35.99 a year to access more features related to photo modification and other tools. It also offers a one-week free trial. After selecting one of the two options, the user is required to upload anywhere between 10 and 20 personal photos taken from different angles to show different facial expressions and reveal their gender. Lensa then processes the photos using advanced algorithms based on Apple’s TrueDepth API.

Lensa uses the techniques of Stable Diffusion and Deep Learning. Like all AI algorithms, a software model like Lensa requires “training” via a dataset to be able to transform the data submitted by users, such as visual materials, into artwork.

These photos are gaining popularity because they offer a service that non-specialized users cannot generate themselves. At the same time, creating these images is simple and straightforward, allowing anyone to use them. However, by collecting this large quantity of personal visual material, these applications raise questions about the security, privacy, and protection of personal data.

The application needs such data to generate the accurate photos that users want, but the problem lies in the data that users share with Lensa and similar applications. This data – which consists of photos – is used by the developers to train their AI model. In other words, personal photos become resources that drive the company’s projects and profits, according to the technical team at SMEX.

“The data and facial features collected by these applications can be used to develop surveillance technologies capable of detecting and identifying individuals, making it easier to track and monitor them,” said Ragheb Ghandour, a cybersecurity expert at SMEX. “This data can be sold and traded with other entities to be used to spy on users.”

After many complaints around the world, the company updated its privacy policy a few days ago to “provide a higher degree of clarity to customers, specifically when it comes to the use and understanding of legal language and terminology,” according to company spokesperson Anna Green. The updated policy also explains that no user data is used to train Prisma Labs’ AI products, contrary to what the previous version of the privacy policy had stated.

Contradictory Privacy Policy Provisions

The app processes the uploaded photos using the algorithms offered by Apple’s TrueDepth API, but its privacy policy lacks clarity and transparency. Therefore, according to Ghandour, users’ faces are stored in Apple’s database.

All facial features are extracted from the photo: facial position, orientation, topology (elements), and other analytical data that distinguish each person’s face. Lensa claims that it does not have access to the photos, but it does indicate that it can access “anonymized” data without offering additional details.

Lensa owns the copyrights to any artwork generated by the app using personal photos, according to the company’s Terms of Use, which state that users own “all the rights to their content.” However, the company specifies that it grants itself the right to “a time-limited, revocable, non-exclusive, royalty-free, worldwide, fully paid, transferable and sub-licensable license to use, reproduce, modify, adapt, translate and create derivative works of user photos, without the need for authorization from the original IP owner.”

Some may think that all of this is not cause for concern. But the truth is that Lensa is only one of the dozens, if not hundreds, of websites and apps turning users’ facial data into resources that belong to anyone on the internet. Millions of users already post their photos on various platforms and websites, which means that these photos are already available online. What, then, is the risk? Lensa and similar applications study users’ facial features, what are considered biometric data specific to each individual, just like their fingerprints, to develop their algorithms, according to Ghandour.

In addition, Lensa, Apple, Google and Amazon, which use ARKit – an augmented reality software that helps in quickly identifying the size of objects in the real world – all have access to this data and to the facial features of every user that has uploaded their photos on the app. Lensa claims that it “collects and stores your facial data to process it online,” adding that “[it] also shares facial data and transfers [data] from users’ devices to [its] cloud service providers (Google Cloud and Amazon Web Services) for the same purpose. In this case, the data available to [Lensa] is anonymized (we receive information about your facial position, orientation, and topology in the uploaded photo and/or video frame).”

Marianne Rahme, head of the Policy Team at SMEX, says that “this lack of detail on the storage of user data, in addition to the contradictory provisions in Lensa’s privacy policy, make the app untrustworthy to be processing our personal data, particularly our biometric data.”

What makes biometric data especially dangerous, according to Ghandour, is the fact that it does not change, because people cannot simply change their facial appearance. Therefore, if their biometric data is leaked, they cannot do anything about it, except undergo plastic surgery to radically change their facial features.

Lensa specifies in many sections of its privacy policy that it deletes all the photos it receives after the user obtains their desired product. However, it also states that it stores personal data until the related account is deleted. In addition, the app does not automatically delete accounts as is normally the case; rather, users have to communicate with Lensa via email, which is confusing for them, not to mention that the process can take up to 90 days.

“Stolen” Artworks

With the spread of digitally modified images via Lensa, there have been many posts, tweets, and reports by artists denouncing the “app’s theft of human artwork.” Some remnants of artists’ signatures could even be seen on specific images. That is due to the fact that the app uses open-source Stable Diffusion.

This discussion is raising the question of whether artists can keep up with AI-generated digital images and produce works that are based both on human and technological capacities. According to many artists, this is impossible, because the relationship between humans and AI is “parasitic” in nature, as AI cannot function without human input. In the absence of such information, AI either would not function or would produce distorted content.

Cartoonist Nohad Alameddine describes this new reality as being “provocative,” considering that any visual artwork requires substantial time and effort, while an AI app can generate similar works in a very short time and at very low costs due to their ability to copy and steal human products. He also told SMEX that the service offered by these apps is “a threat to the livelihood of all kinds of artists, as their theft is twofold: first when they steal the artworks, and second when they charge money for the service.”

Alameddine added that “despite the severity of the situation, I believe that these apps will never be able to compete with human capabilities, as AI cannot link together several thoughts to produce a successful visual work.”

The only recourse for artists is to demand legislation that regulates AI-based artistic tools and apps in order to protect their works and prevent companies from using artworks produced by humans to feed and develop their AI models.

As these types of software continue to flood digital spaces, and as major companies find new ways to conceal the flaws in their policies related to users’ digital rights, will personal data protection laws be enough to protect the privacy of individuals and their information?