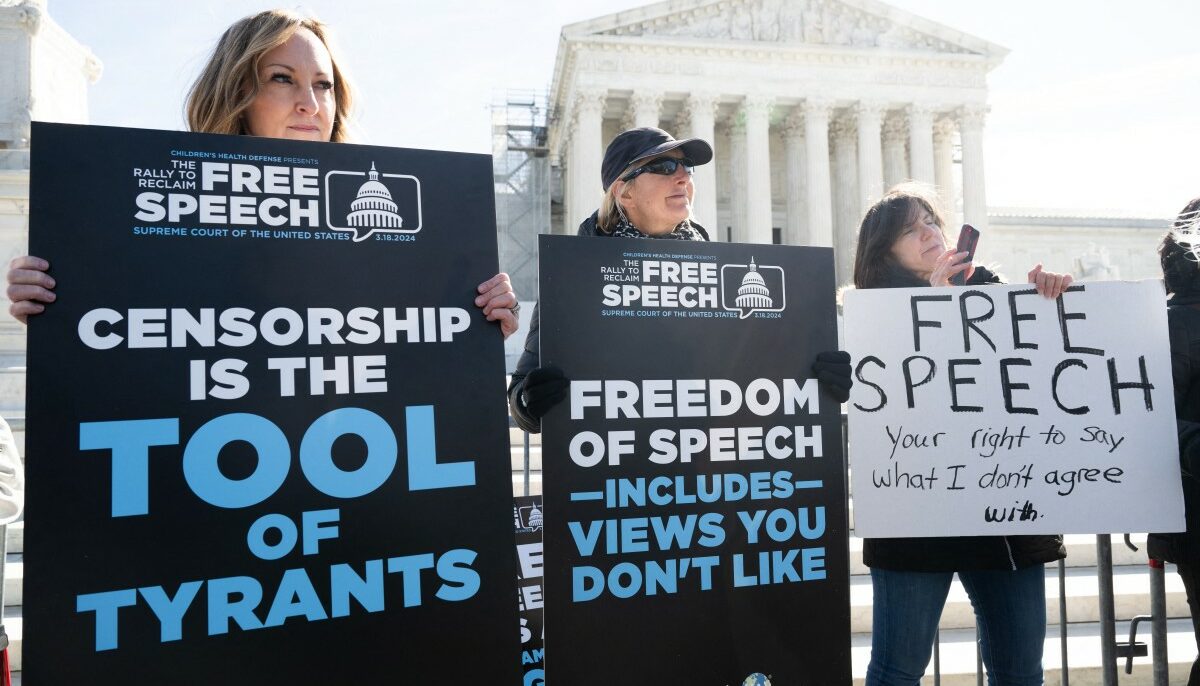

Today, censorship in the US is under severe scrutiny from millions around the world who are witnessing the wave of repression against advocates for Palestinian rights across workspaces and college campuses in America. Internally, however, freedom of expression is considered one of the cornerstones of the country’s legal system. Free speech, as enshrined in the First Amendment of the US constitution, is a guaranteed right and its provision surpasses any legislative authority at the state or federal level.

In this respect, it came as no surprise that the legislator introduced an amendment to the Communications Decency Act (CDA) in 1996 which aims to ensure that providers and users of an interactive computer service were free of any liability related to the content they hosted. In other words, the hosts of online content were no longer responsible for the content published via their platforms and services. This has been the norm ever since.

The CDA’s purpose was to regulate sexual material online by making it illegal to intentionally send offensive or indecent material to minors or allow them to view such material online. However, the introduction of the notorious Section 230 as an amendment to this Act was deemed necessary to guarantee that internet services were free to select the kinds of information they host. Without this legal provision, websites that remove sexual content could be held legally liable for doing so, possibly leading to the websites’ reluctance to remove such content out of fear of being punished. This would ultimately undermine the very essence of the CDA’s aim to create a safer online space for minors.

This article gives a comprehensive overview of the Sections’ provisions and explains the exceptions to its scope, as well as the attempts to change it. How relevant is it today? Should it continue to be applied as is or should it be modified?

Section 230’s provisions

Section 230 establishes two separate provisions for the provider or user of an interactive computer. First, Section 230(c)(1) states: “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.” In the spirit of this provision, the only entity responsible for the content shared is its creator, not the provider or user.

The first case interpreting this provision was the Fourth Circuit’s 1997 decision in Zeran v. America Online, Inc, in which the federal court rejected the plaintiff’s argument that AOL, a bulletin board where an ad about him was published, was a distributor and not a publisher [Section 230(c)(1)]. In the court’s rationale, the term “distributor” falls under the scope of the term “publisher” and is thus protected by Section 230.

Second, according to Section 230(c)(2), users and service providers are exempt from liability if they, in good faith, voluntarily limit access to material that is considered “obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, excessively violent, harassing, or otherwise objectionable” and if they provide “the technical means to restrict” access to this material.

Paragraph (B) of Section 230(c)(2) allows content providers to offer users the choice to opt in or out of receiving certain kinds of content. For example, it allows providers of programs that filter adware and malware to restrict access to offensive material. In line with this, jurisprudence has also treated big tech companies, such as Meta, as eligible for immunity under Section 230(c)(2)(B), provided that they offer users the option to conceal or otherwise limit their own access to content.

The requirement of acting “in good faith” when restricting access to content does not apply to Section 230(c)(2)(B), which may lead to potential abuse of the provision for conduct that seeks to employ anticompetitive blocking. Such was the case in Enigma Software Group USA, LLC v. Malwarebytes, Inc., in which the Ninth Circuit found no immunity under Section 230(c)(2)(B) for a competitor company that started flagging some of the plaintiff’s programs as “potentially unwanted programs,” to harm the competitor’s business.

Exceptions to Section 230 immunity

Although Section 230 acts as a warden for freedom of expression, its immunity is not absolute. Paragraph (e) enumerates five exceptions which would bar such immunity. Firstly, the provision does not apply in federal criminal prosecutions, such as cases of known distribution of obscene materials online or money laundering. The second exception relates to “any law pertaining to intellectual property.” Although the phrasing of this exception has been considered vague and ambiguous, the courts’ interpretation in several cases, such as Enigma Software Group. USA, LLC v. Malwarebytes, Inc., demands that the plaintiff’s claim actually entail an intellectual property right. Pursuant to the Ninth Circuit’s ruling in Perfect 10, Inc. v. CCBill LLC, the exception applies only to “federal intellectual property.”

Next, Section 230(e)(3) affords states with the margin of appreciation in enforcing state laws consistent with the Section without further explaining what this “consistency” requires. This means that states can decide on applying their legislation as long as it is consistent with Section 230, but the provision does not set out specific criteria to assess the consistency. For such an evaluation, courts have turned to assessing whether defining service providers or users as the publishers of content created by others would violate Section 230(c)(1).

The fourth exception is related to claims brought under the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 (ECPA), a federal law about wiretapping and electronic eavesdropping, “or any similar State law.” The ECPA contains both federal criminal offenses and civil liability provisions, falling under the first and the fourth exception of Section 230(e) respectively. While under the ECPA, it is illegal to knowingly intercept covered conversations, as well as deliberately reveal information if one “ha[s] reason to know that the information was obtained through” an unlawful interception. In one instance, a company provided web hosting services to people who sold illegally obtained videos, and the Seventh Circuit rejected the argument based on Section 230(e). In the court’s view, the web service providers could not be held liable for assisting the perpetrator, since there was no hard proof of the former “disclosing any communications.”

The last exception of Section 230(e) is a product of the Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act of 2017 (FOSTA) and concerns sex trafficking offenses where it applies when it can be proven that only one of the three provisions of Section 230(e)(5) has been violated. The difference between the elements of these provisions, especially the mens rea required, created an ambiguous evaluation and resulted in diverse interpretations by the courts. For the Ninth Circuit, Reddit’s “mere knowledge” of unlawful content involving child trafficking on its platform was not deemed sufficient for the application of the Section 230’s fifth exception.

Attempts to modify Section 230 due to concerns about it providing impunity

Despite its inarguable contribution to protecting freedom of expression, concerns have been raised regarding Section 230 providing platforms with almost full impunity when it comes to accountability. Even though big tech companies have gained significant influential powers and while their users have benefited greatly from their services when it came to utilizing a space to communicate and get organized, as was the case in the Arab Spring, the #MeToo, and the #BlackLivesMatter movements, there are still some serious drawbacks that need to be addressed.

Complete platform immunity can have detrimental consequences to online users. Without facing liability, platforms are more reluctant to moderate harmful content that does not fall under the Section 230 exceptions. For example, the Capitol riots were facilitated by social media while hate speech from white supremacists still flourishes online. Big tech companies are generally driven by profit, resulting in human rights playing a secondary role in their decision making. This means that vulnerable groups may be “sacrificed” when there is money to be made. In addition, social media policies are often based on US politics and harbor significant western biases against certain populations, most significantly the Arab-speaking communities, which can lead to over-moderation. This is the case with the Meta’s Dangerous Organizations and Individuals Policy that puts in danger specific groups and clearly demonstrates bias against particular communities in the WANA region, such as the Palestinian community. Not abiding by any legislation regarding content moderation is extremely hazardous and can eventually lead to narrow interpretations of freedom of expression online, as the recent Meta over-moderation of the word “shaheed” has shown.

Due to these concerns, there have been several attempts to modify Section 230. In April 2023, Senators Lindsey Graham (R-SC) and Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) introduced the EARN IT Act, which aimed at removing Section 230 immunity for platforms that failed to identify and remove content containing child sexual assault. During his presidency, Donald Trump issued an executive order, which was later revoked by Biden, that only protected platforms with “good faith” moderation by Section 230 safeguards, and then urged the FCC to establish guidelines for what qualified as good faith. On a state level, Florida and Texas also tried to limit the scope of Section 230 by adopting two laws, both of which are now inactive, that prohibited social media platforms from respectively banning politicians or media outlets and removing or moderating content based on a user’s viewpoint.

Modifications to Section 230 may seem crucial, with platforms constantly gaining more power in the sphere of content moderation and thus shaping politics and threatening the protection of human rights, especially that of the most vulnerable people. However, it is vital that any potential changes do not hamper freedom of expression by annihilating the very essence of the provision. In an evolving world of continuous developments, rights and freedoms of all people, but most importantly of those in greater need, must be the guiding light when reconsidering legislation. On the other hand, leaving it entirely to the private initiative to regulate themselves can prove extremely dangerous, as their motives tend to fall far from the needs of their users. It is therefore of the utmost importance that platforms comply with international standards regarding freedom of expression and content moderation and that the international community, together with civil society, work tirelessly to ensure such compliance.