Can you imagine going on the web to find an ocean of knowledge, but you can’t read any of it? This is the everyday reality for someone with aphasia, a communication disorder that can affect speaking, reading and writing.

As someone with post-stroke aphasia, I find it difficult to read web text with small font and narrow spacing, while I have fewer problems with writing. Did you know that less than 1% of websites meet reading-accessibility standards? That leaves me without access to almost 1.8 billion websites on the Internet today. To read online content, I have to copy it into google docs and spend so much time changing the font’s size, text and color, and fixing spaces.

Information on the web should be accessible to all, including people with language disabilities. The Internet is a crucial resource in our interconnected world today. It is a space for network-building, a pool of opportunities for job-seekers, and an indispensable source of knowledge.

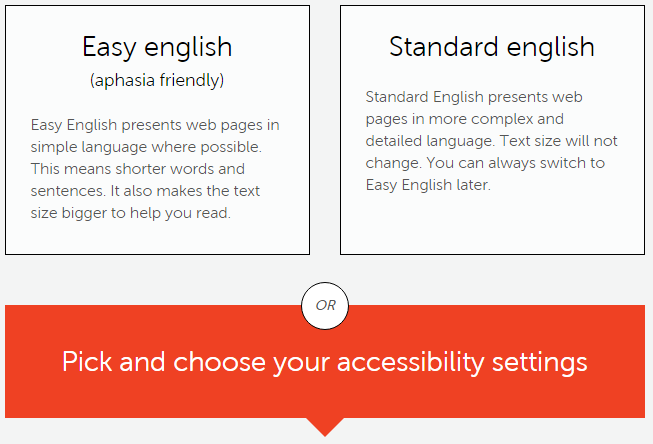

Despite the Internet coming a long way since its conception, it is still largely inaccessible to people with language impairments such as aphasia, dysphasia, and dyslexia. Although approximately 18.5 million individuals have a language disorder, few developers, designers, and content producers respect and consider these differences. Websites such as enableme, Bookshare, Online OCR, and Microsoft OneNote are some of the few that offer features for people with language impairments.

Language Disability from a Legal Perspective

People with language disabilities have the right to inclusion and equitable access to the Internet. Lebanon adopted Law 220 on the Rights of Disabled Persons (Law 220/2000) several years before the adoption of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disability (CRPD). It states that: “To enable persons with disabilities to live independently and participate fully in all aspects of life, States Parties shall take appropriate measures to ensure to persons with disabilities access, on an equal basis with others, to the physical environment, to transportation, to information and communications, including information and communications technologies and systems […]”.

(Image via enableme.org.au).

Language Accessibility Tools

Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) covers a wide range of recommendations for making the Internet content more accessible to a wider range of people with disabilities, including blindness and low vision, deafness and hearing loss, learning disabilities, cognitive limitations, limited movement, and speech and language disabilities. According to WCAG, every website should:

- contain alternative texts for all non-text elements

- provide access to all functions from a keyboard

- provide readable and understandable text content

- ensure that each page can be operated in a fully predictable way

- ensure that users can correct their mistakes

- give users enough time to read text content

- provide correct heading structure

- use contrast colors

- enable resizable text

- make video and multimedia accessible

- minimize the use of tables

If you are a designer or a developer, consider running your website through WebAccessibility’s tool to test if it meets WCAG standards. And if you have a language disability, use accessibility features in modern browsers such as “text font” (Firefox, Chrome, Safari) and “enlarge your view” (Firefox, Chrome, Safari).

Living with aphasia is harsh, but it can be made easier through thoughtful coding and inclusive design. When your content features options for people with language impairments, we feel seen and respected. After all, it is our collective responsibility as policy-makers, designers, and developers to keep the Internet accessible to all, despite our differences.