On May 5, MTN Sudan announced that all its relay stations in Khartoum were down due to power outages and difficulties in transporting fuel for generators. NetBlocks, a watchdog organization that monitors internet traffic globally, declared on April 30 that MTN experienced a brief collapse in connectivity on Friday due to a shortage of energy supply.

Telecom services quickly deteriorated less than 48 hours into the conflict. The electricity purchase system broke down, leaving citizens in a total blackout after their supply balance ran out.

Without fuel and electricity, workers and engineers could not commute to do necessary repairs, suspending basic services such as ambulances. The decision to shut down the internet only made things worse. Sudanese citizens often use the internet to ask for aid, food, and medicine, as well as to search for missing persons.

Lack of Security and Supplies

A trusted source told SMEX that the power outage caused instability in services at one of the main data centers of Canar Telecommunication Company. Having an offshore station, it is the second largest service provider in Sudan. This affected the efficiency of services provided by other companies and interrupted Canar’s 4G network. The company’s engineers could not reach the data center, located within a flashpoint near the Radio and TV headquarters.

Eyewitnesses confirmed to SMEX that the satellite station in Umm Haraz, south of Khartoum, was pillaged due to the deterioration of the security situation and the absence of guards.

Supply shortage also shut down all online banking applications, including Bank of Khartoum’s “Bankak,” a lifeline for Sudanese citizens who use it to make online payments. The app was down for almost two weeks before being reactivated.

Technical Malfunctions

Due to the conflict, Sudanese citizens cannot access internet services via USSD, a GSM protocol used to purchase services such as telecom balances. The interruption lasted several days until Zain Sudan offered free access to WhatsApp.

In addition, social media users complained about interference on phone lines, raising concerns about a potential breach of users’ privacy and a possible threat to their lives amid such circumstances. It is worth noting that Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces (RSF) uses Israeli spyware Predator, one of the world’s most advanced and most dangerous spyware.

On April 16, Reuters quoted an MTN official saying that the authorities gave them a directive to block internet services in the country before being told to restore them a few hours later.

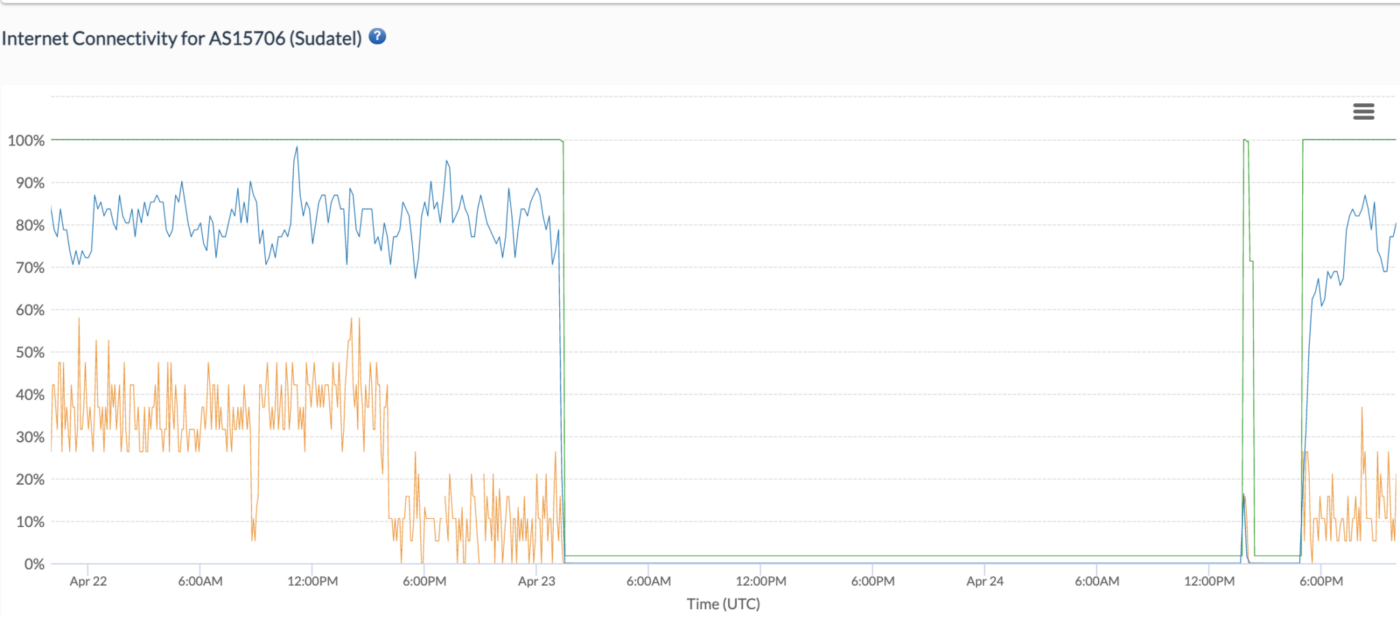

On April 23, the Sudanese Armed Forces announced that the RSF occupied Sudatel Center, the oldest telecom exchange building in Sudan housing the data centers of government-owned Sudatel (Sudani). This shut down the company’s telecom and internet services and isolated users from the rest of the world.

Screenshot from IODA showing the shutdown of Sudatel’s internet services on April 23 and their return on April 24.

Screenshot from IODA showing the shutdown of Sudatel’s internet services on April 23 and their return on April 24.

Internet and telecom outages are not new for the Sudanese people. Over the past four years, citizens have gotten used to internet shutdowns based on government directives in times of crisis. In 2022 alone, the Sudanese authorities shut down the internet on five occasions. Citizens expected such outages from the first few hours of the current military conflict.

The party controlling the telecom networks in Sudan is the Telecommunications and Post Regulatory Authority, which operates under the supervision of the Ministry of Telecommunications. In a previous report, SMEX revealed that the authority is in fact subject to the Sudanese Armed Forces, especially since the Director-General of the Agency, Major General Al-Sadiq Jamal Al-Din, is a high-ranking officer in the military.

Disinformation and Breach of Privacy

The transmission of Sudan’s radio stations and state TV was interrupted as the conflict raged. Some claimed this was due to the RSF’s takeover of the Public Authority for Radio and Television headquarters. The RSF used the 95 MHz frequency of the national radio station to broadcast news of its “victories,” while the Armed Forces took control of Sudan TV’s satellite transmission.

Interruptions in the radio and TV transmissions, lack of transparency, and the use of media disinformation as a military weapon provided fertile ground for spreading fake news. A prominent example was the Twitter account of Sudan’s General Intelligence Service (GIS), which published tweets containing statements in the name of the GIS, before the GIS itself denied having anything to do with this account.

Some citizens are documenting violations committed in their regions amid the lack of objective media coverage – that is, if journalists can reach conflict zones in the first place. Eyewitnesses told SMEX that the RSF is demanding access to the contents of citizens’ phones and committing acts of violence against them.

A media expert who wished to remain anonymous for security reasons said that phone searches are likely an attempt by the RSF to polish its image–mainly by deleting any incriminating content. Several reports have confirmed that the RSF has been working with media centers abroad specialized in disseminating propaganda to improve its reputation. That could explain why internet services were restored for certain periods instead of being completely cut off, in total disregard for people’s suffering.