For the past month, disinformation has been raging across social media platforms in Sudan. The Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) compete to control the online narrative, no matter the cost.

The problem of fake news and misinformation has always plagued Sudan’s digital spaces, becoming most harmful during armed conflict and political unrest. On the one hand, the RSF heavily relies on tweets and inauthentic behavior to spread its agenda and influence local and international opinion. To a lesser extent, the Sudanese army uses Twitter to refute RSF claims and boost army morale with false victory claims.

Information war on Twitter

Often run by government organizations and political rivals who aim to spread their propaganda, disinformation is false information intended to mislead. One of its most tragic consequences is that it endangers the most vulnerable. During times of conflict or displacement, when access to necessities like food and water is limited, people often rely on information from official sources on social media as a lifeline.

“Those seeking refuge from the conflict turn to social media for updated guidance and resources; fake accounts misuse this public panic and exploit and mislead those in need,” said Azaz ElShami, a Sudanese-American human rights advocate and independent consultant interviewed by SMEX.

Blue-ticked and with over 100K followers, the RSF’s Twitter account and online support network play a key role in spreading disinformation. The page runs unhinged on Twitter, although the paramilitary group has committed countless crimes against humanity in Sudan, raising serious questions about the platform’s commitment to safeguarding human rights.

Twitter has aided the RSF by allowing it to exist officially online and giving it a virtual platform for setting its agenda. For example, the most recent assault on the Sudanese capital on May 12 was marked with aggressive tweets by the RSF falsely claiming complete control of Khartoum and other misleading information. However, trusted media agencies and sources close to SMEX reported ongoing fighting in the capital, contradicting the RSF’s claims.

Screenshot taken on May 10, 2023 of official Twitter account of the RSF

The RSF also launched a defamation campaign against the Sudanese army on Twitter, accusing it of targeting civilians. These statements were disseminated in both Arabic and English to manipulate public opinion locally and internationally.

Video of the RSF claiming complete control of the capital on May 12, 2023

“The conflict in Sudan is very polarizing, and the political narrative is divisive,” Azaz ElShami told SMEX, explaining how the RSF is using Twitter to construct a problematic online narrative. SMEX’s digital research consultant scrapped and textmined RSF Tweets between May 15 and April 15, 2023, revealing RSF’s agenda-setting strategy. Some examples of the most frequently used hashtags include:

| Arabic | English | Percentage |

| قوات_الدعم_السريع | Rapid Support Forces | 20% |

| حراس_الثورة_المجيدة | Guards of the glorious revolution | 14% |

| معركة_الديموقراطية | The Battle for Democracy | 14% |

Most frequent hashtags between April 15 and May 15, 2023, RSF on Twitter

Idealizing the RSF’s leader Dagalo and his role in their military assault and calling it a “revolution” and a “battle for democracy” in the hashtags is deceptive, considering that the RSF is a paramilitary group trying to hijack political power by force. Over 15% of RSF’s tweets published between April 15 and May 15 are in English, focusing on spreading false information about the Sudanese army, presenting the latter in a misleading light to an international audience.

In other examples, the RSF uses civilians’ statements as propaganda videos, where they film merchants and drivers living “normally” under RSF control, misleading the Sudanese people and manipulating public opinion to their favor. In reality, RSF fighters have been setting up bases in residential neighborhoods and people’s homes to gain an advantage over the SAF’s heavy weaponry.

On the other hand, the Sudanese army employs defensive disinformation tactics to maintain troop morale and public support for the government. Unfortunately, this approach poses significant harm to the local population, placing particularly vulnerable groups at risk.

Digital rights expert Khattab Hamad, interviewed by SMEX, highlighted disinformation cases that posed significant risks to the livelihood and safety of Sudanese people. One example involved the Sudanese army falsely claiming to have regained control of the main building of the Radio and TV station in the capital, when in fact they did not.

SAF claiming they have captured and secured the main TV and Radio building in Khartoum, April 17, 2023

Such fake proclamations of victory give citizens and journalists the illusion of safety when there is still danger on the ground, rather than warning them to be more cautious. A local source told SMEX that one journalist working for a local news agency visited the Radio and TV building right after the announcement, only to meet RSF fighters, an encounter that could’ve been deadly.

Lastly, the Sudanese army falsely claims that the Sudanese capital and other areas are safe, despite being a battleground for both armed forces. According to Khattab, such claims have placed many families in imminent danger, especially those displaced to other regions. Tweets and official statements from the SAF and affiliated pages describing the battles as “very limited skirmishes” undermine the severity of the fighting and place millions of lives in danger.

“Conflicting information and polarizing propaganda create confusion and could lead to actual harm on the ground. For example, when an entity that appears to be official announces that an area is clear, many volunteers take it as a fact and dispatch help to assist potential victims,” said Azaz ElShami.

Another example of conflicting narratives on social media by Beam Reports, an independent Sudanese media platform, highlights conflicting claims from both SAF and RSF about controlling the strategic Marwe air base in Northern Sudan.

One undefined source shared a fake video on Twitter showing civilians resisting the RSF by throwing stones at one of their vehicles. The actual video has an entirely different context, dating back to the 2019 protests during Sudan’s attempted transition toward democracy after overthrowing Omar Bashir.

Fake video published on 25th Apr 2023

Original video published 18th Mar 2019

This video is particularly dangerous as it might encourage civilians to take it upon themselves to face paramilitary forces on the ground, leading to fatal repercussions. This video, published on April 25, 2023 is still running on Twitter.

At the same time, internet shutdowns in the country have left millions of Sudanese helpless against the early fake news campaigns, as people cannot double-check facts or contact others to verify data.

Twitter’s role in the disinformation warfare in Sudan

According to a coda report, a fake Twitter account, falsely posing as the official RSF one in Sudan, gained traction due to Elon Musk’s monetization of the blue tick. It falsely claimed the death of the RSF leader, which would have been a game changer for the conflict in Sudan.

This highlights how profit-driven policies on Twitter have enabled the spread of disinformation during the Sudanese conflict endangering millions of Sudanese people through the manipulation of information.

“Twitter had responsive and adaptive site integrity measures that were informed about malicious campaigns. Reinstating similar policies is necessary, especially when the content could lead to actual harm in conflict zones,” ElShami told SMEX.

These regressive policies by Musk also include promoting government-linked pages, as well as restrictions on Twitter API. Although this one account reported by CODA was removed, many others are still involved in spreading harmful disinformation in Sudan.

The DRFLab has reported inauthentic activities involved with the RSF twitter pages, with at least 900 potentially hacked Twitter accounts constantly retweeting and engaging with RSF accounts, creating an illusion of popularity online.

“Coordinated inauthentic behavior campaigns have been one of the main techniques malicious actors use to manipulate the algorithms of social media platforms to boost their engagement online, which is what we are witnessing in Sudan right now,

Wafaa Heikal, social media analyst with Democracy Reporting International, told SMEX. “It’s a battle of controlling the narrative especially in front of the international community,” Heikal added.

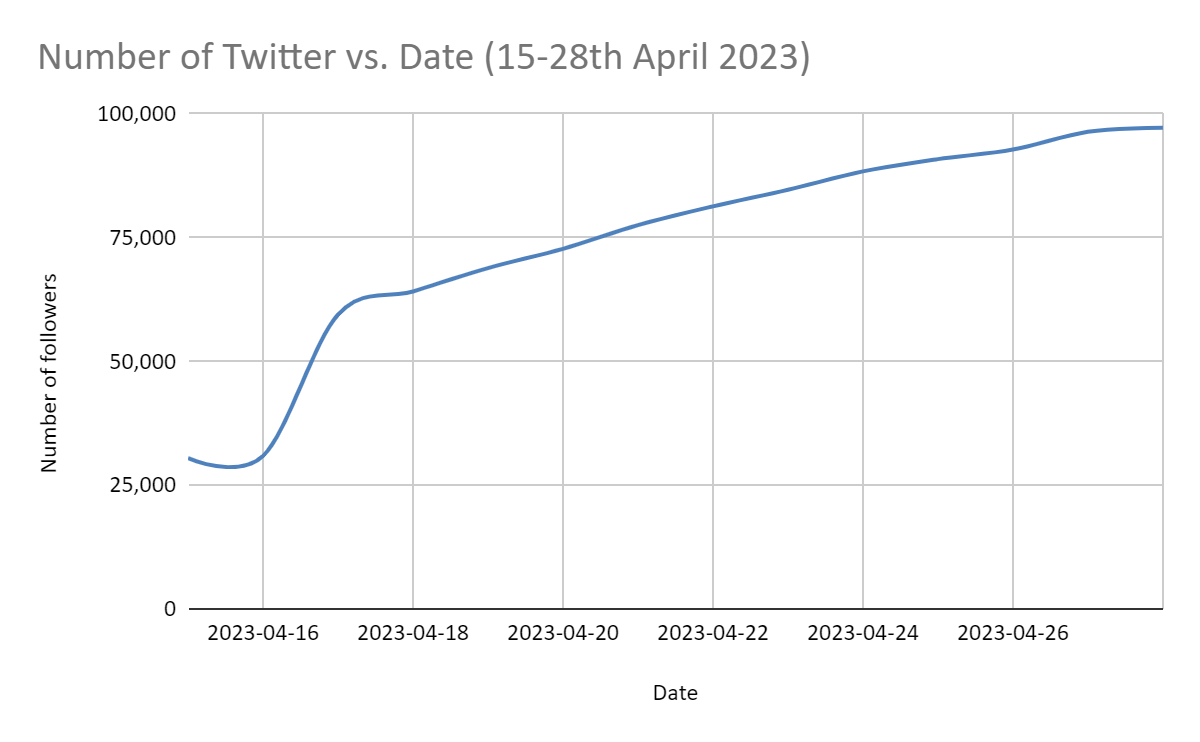

The hacked accounts discussed before are boosting RSF twitter engagement as well as their followers’ base. According to social blade analysis of RSF on Twitter:

Number of Twitter followers over time (15th-28th of April 2023)

The RSF page managed to increase its base of followers by more than three folds in less than two weeks, an indicator of a successful campaign in leveraging Twitter’s new policies to serve their political goals.

Prior to Musk’s takeover, Twitter’s management and staff were well aware of the risks posed by coordinated inauthentic behavior (CIB) in influencing public opinion. For example, Twitter removed 5,929 accounts linked to a state-sponsored operation from Saudi Arabia, boosting the county’s political agenda on an international scale.

TikTok performed slightly better than Twitter in the case of disinformation in Sudan. Tiktok offers API access for U.S. based researchers, which allows researchers to investigate and report CIB networks as well as other malicious actors.

The popular platform’s clear content moderation guidelines explicitly forbid threats, violence, and promotion of violent extremism, including organizations and individuals associated with such actions. However, Tiktok is still rampant with viral videos, pro and anti-RSF, that promote harmful content and must be removed from the platform.

Pro RSF & Anti RSF viral TikTok videos:

| Theme | Views | Engagement (likes, shares, comments) | Link |

| Pro RSF: Military music video promoting | 460K | 10.6K | https://vm.tiktok.com/ZGJmNcvhc/ |

| Anti RSF: death of RSF leader | 2 million | 8K | https://vm.tiktok.com/ZGJmNsHB8/ |

| Anti RSF: Claim to be from RSF leader’s house | 2.5 million | 17K | https://vm.tiktok.com/ZGJmjfJgq/ |

Pro/Anti RSF TikTok content (15th April – 15th May 2023)

These problematic statements have been supported by a fleet of TikTok videos, some of which claim the death of RSF leader to sway public opinion in favor of the Sudanese army.

This video had more than 2.5 million views on Tiktok, manipulating the opinion of millions of Sudanese and placing them at risk.

“The fact that TikTok and Twitter are very popular among the youth in Sudan, who are spearheading humanitarian response, is amplifying the crisis of disinformation on social media,” said Azaz ElShami.

Disinformation: a machine gun powered by algorithms

Disinformation campaigns have immediate and severe consequences for individuals during times of unrest. Fake news not only endangers the lives of vulnerable communities, but also disturbs humanitarian work.

Twitter’s policy changes, such as monetizing the blue badge and restricting API access, have unintentionally facilitated the spread of disinformation. While civil society organizations and responsible media agencies advocate against war, their voices often get overshadowed by algorithms favoring state-run news agencies and aggressive social media campaigns.

Digital literacy programs designed in partnership with tech companies can help mitigate the harms of disinformation and facilitate prompt humanitarian aid in conflict-affected areas, as TikTok did in the case of Ukraine.